One could be forgiven for thinking Indian minimalism is a bit of a contradiction in terms, but, in a nation known for layers upon layers of decorative details, designers like Sanjay Garg are honoring Indian traditions while striving for an aesthetic which feels fresh and modern. Using handloomed silks and cottons in luscious colors, Garg’s brand Raw Mango produces saris that are ethereal. Luxurious, but not glitzy. “We do not believe our designs need to be kitschy to be Indian”, the brand’s website states. There are no heavy embellishments, flashy marketing campaigns or advertising. Though Raw Mango can be purchased at Good Earth and a few other retail outlets in India, no more than a small percentage of the collection is sold outside of the showroom.

Garg’s workspace and showroom at the Ansal Villas at Angoori Badi Farm in the Chhatarpur area of New Delhi is all white and styled minimally. There is a low sofa, a natural wood table, and a jute mat on the floor. But when Sanjay opened the cupboards for us on a recent visit, a bright burst of light and rainbow of colors spilled forth. Neatly stacked silk saris and dupattas were swept from the cabinet and arrayed in front of us for our admiration.

As we sat and talked with Sanjay over tea, discussing travel, music, and ethical business practices, it became clear that Sanjay is as thoughtful as he is energetic. He is a curious soul who pours over history books and travels at home and abroad for inspiration.

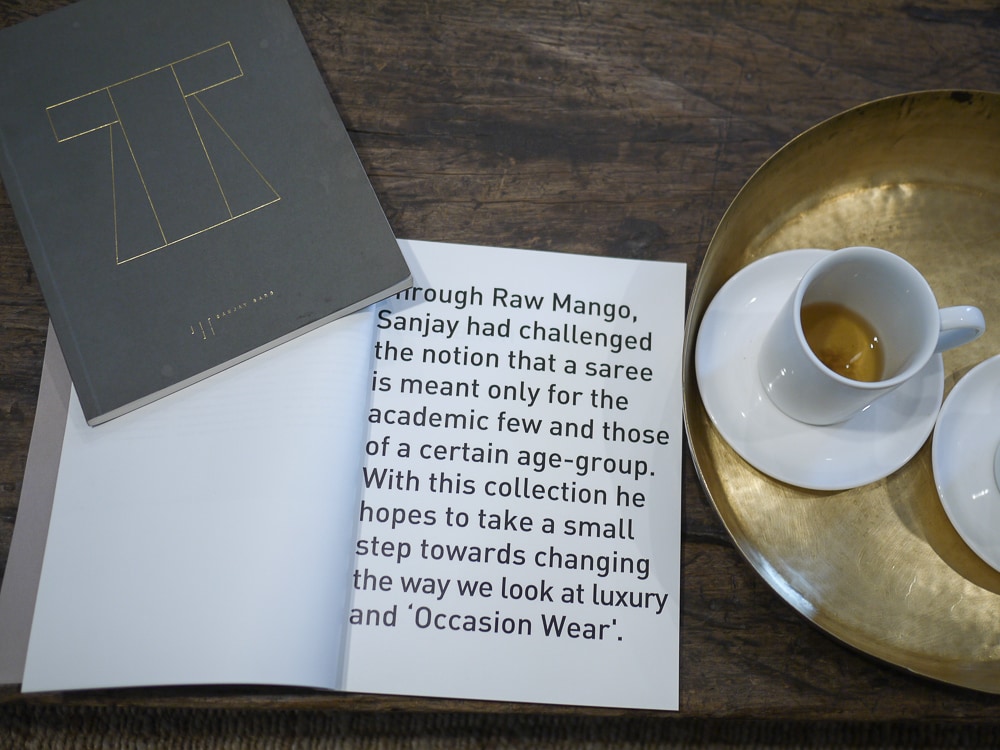

In addition to creating textiles for draped saris for Raw Mango, Garg also designs Sanjay Garg, a stitched collection inspired by traditional Asian shapes. “This shape came from the Middle East. If you make it very long, it's called an abaya, and when you make short it is Indian shape. And, if you make the shape bigger it becomes a kimono if it’s cut in this way. If you make this into a triangle, it becomes a Chinese garment,” he said pointing to the gridded shape on the cover of his lookbook. “Everything is worked around this Asian garment shape. So my inspiration is really my love of history and culture.”

Sanjay started his business with only four weavers in Chanderi in central India. “They were not even master weavers,” he said. He didn’t want to involve himself with the NGOs that are plentiful in India, but rather strove to be self-sufficient. Of the original weavers that joined his business in its first days, one had previously worked as a house builder and another was a security guard. “So one guy looked after production, one for accounting. Of the four people who came together to start the business, each guy was looking after 25, 30 people. They decided their wages themselves, they bought the yarn. I told them where to go, and how to do things, but they started as four and dedicated two rooms of their house to it.”

He now employs over 450 artisans who use traditional techniques to create his contemporary textiles. These weavers work primarily at home in a village setting, but Sanjay chooses not to highlight this aspect of his business to avoid sentimentality. “I don't want my business to run with [poverty] sympathy,” he says, “but I do want to celebrate their skill set and strength, the uniqueness of the way they weave.”

Garg wants his handmade products to stand up to those made by machine: “If your product cannot compete with a machine, if your hands can not create something very special which a machine can do, then you have no right to do it. You have to give it uniqueness if you want to create something very special…”

While Sanjay doesn't make his own story – or that of the weavers – part of his brand, he is proud that the four original business partners that have improved their living conditions. “So now those weavers have an eight bedroom house. Look at the color television and the refrigerator!” he said excitedly, pointing to photos on his mobile phone. “And they had nothing, not even a fridge, three years ago. Cold water was sheer luxury in 40 degree Celsius weather then. This is something I can't fabricate. I don’t want a [NGO style] report, I want something as authentic as this. I want a report like this.”

To him, doing business and running an ethical business are one and the same: “The big thing that everyone is discussing right now is that if your turnover is more than certain amount, then you have to give 4% of that profit to CSR. I say “So what do you mean by CSR - that you can do whatever wrong-doings you’d like, and then you give 4% and you're done?” He asks “Is business separate from an ethical business? I don't understand this division.”

“I'm asking a big question: why would you not have ethical business practices in your day-to-day life anyway?”