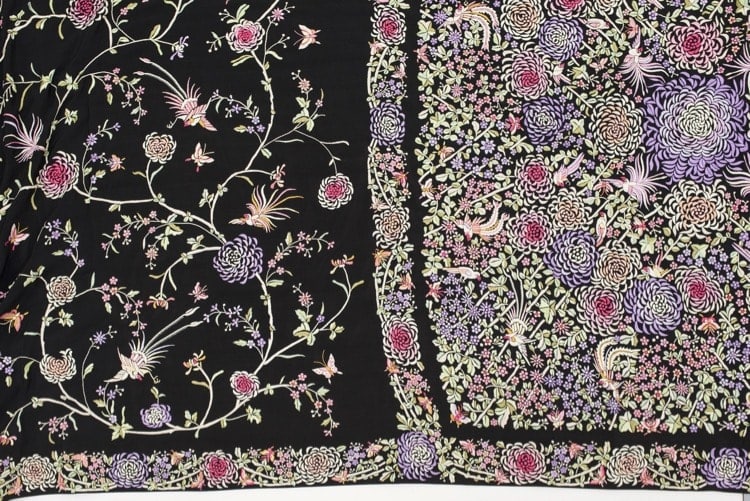

Sometimes it's the most familiar things which contain the greatest capacity to surprise us. While traditional forms of dress fade from view all around the world, the sari remains widely worn throughout India and South Asia. And yet despite these deep roots, even those who wear the sari can sometimes harbor narrow views about when — and how — to wear it.

Malika Verma Kashyap is challenging those preconceptions. ‘The Sari Series: An Anthology of Drape’ is a new, non-profit initiative spearheaded by Kashyap and her team at Border&Fall. Intended to explore new possibilities for the historic garment, the project documents a panoply of regional sari draping styles in the form of 80 short demonstration videos. The group also commissioned three short films which suggest new aesthetic concepts to refresh how the sari is visually represented.

Created with the help of an all-star team of advisors like Sanjay Garg and Rta Kapur Chishti (perhaps India's leading authority on the sari), these resources are intended to start a conversation — one which might help people to see the sari with fresh eyes and also, perhaps, to take a moment to consider its future.

THE KINDCRAFT recently talked with Kashyap to learn more about the two-year process of bringing ‘The Sari Series' to life.

THE KINDCRAFT

You've written that you've wanted to do this project as far back as you can remember....

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

I think that quote speaks to my relationship with the sari. It's been around me for as long as I can remember. I mean, one, in terms of being Indian and that it's a part of our lives. And then, two, as something I've personally been connected to. I remember when I was five, my grandmother had come to visit us in Montréal from Delhi and she said "Design whatever you want and I'll have it made”. And I remember drawing a really long, rectangular sari — in orange with a yellow border — and that's what she brought for me. "Border&Fall" itself is named after various parts of the sari.

And so I look back and I basically see the sari as having been very close to me without it being, like, my raison d'être. It's not something I've ever been a champion for, per se. I haven't worn saris every day, all my life, and I haven't been vocal about it — it's just been there.

Of course, I'd worn a sari throughout my life as occasion wear, but I very much remember the shift to daily wear [arising out of] a very conscious conversation I had with a friend of mine whose family owns one of the oldest sari shops in Bangalore. We were surrounded by these gorgeous saris and said "we've got to start wearing saris every day" and were wondering how to do it. And then I saw her a week later and she was wearing a sari. I was, like, "What are you doing? When did this happen?" and she said "It started a few days ago. Really, it's not a big deal..." And that's how it started — because it is a big deal — especially when you're [shifting from] wearing it as occasion wear to day wear.

Then, on top of it, we feel like there's one correct way of wearing it and that's where this project took hold — in the sense that we impose this rigidity on a fluid garment, quite literally. If you ask most anyone to draw a sari, their images would probably look the same. We have a huge opportunity to address a way forward through looking at the past.

A Shift In Perception...

THE KINDCRAFT

What are your goals for ‘The Sari Series'?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

There's two real parts to this project: One is a cultural documentation to create a body of work which did not exist. And the second was to speak to a needed perception shift of the garment, [asking] "Can people look at it as more than what they think they know of it?"

Rta Kapur Chishti's involvement has been integral to this project and she, hands down, was the first person I reached out to and I couldn't imagine doing this project without her. She's spent her life documenting these drapes and so the knowledge comes from her research and she gets 100 percent credit for that. I wish more people knew about her work and, hopefully, this is another way in which it will be acknowledged.

We named it "The Sari Series: An Anthology of Drape" and not "The Definitive Anthology of Drape" because there are so many drapes that exist which we're not aware of — and because draping will continue to evolve. I mean — How amazing would it be to see someone invent their own drape and wear it in a way that's not one of these things?

THE KINDCRAFT

Is that second goal an attempt to get more people to wear the sari?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

By no means is this tied into a "Save the Sari" conversation — that's never been the focus or the narrative of our work.

The project is a perception shift — definitely not about getting people to wear the sari again or saying "let's look at draping in a different way" and that's the answer. I certainly don't want to be in any position to dictate what people should be wearing or what they should be feeling about one's culture or dress. That's an individual thing.

So when people ask "Do you think people will start wearing the sari [as a result of the project]?" I always say "I don't know—it's not one of the aims." I think it would be very ambitious to say this work would shift that. However, can people view this project and shift what they know about sari? Where it feels more accessible to them? As a garment, as an idea, as something they can wear or see at home... and just look at it differently? I think maybe it can speak to that and, for me, is a goal.

THE KINDCRAFT

I've read other interviews where you've said it's difficult to claim there's a need to "Save the Sari" when it's something millions of women are currently wearing. Since the goal of this project is perception shift, isn't showing that wearing a sari doesn't necessarily require 15 safety pins and a petticoat mean you're advocating that it's a garment compatible with everyday wear and not just for occasions?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

It's about showing people, not about dictating. It's just pointing out the actuality of it, not leading someone. You can reach your own conclusions, right? Out of every film we've done: not a single one has a safety pin, not a single one has a petticoat, some of them don't have blouses. I think there's a lot a lot to learn there...

Those of us who worked on the project — we've seen that ourselves. We've been wearing saris in different drapes for many years and it's amazing — we've seen that potential for transformation personally, when we drape friends or when we meet people while we're out who say "I would wear a sari if I could drape it like that." and, suddenly, they see it. And I've been asked many times when I wear a sari "What are you wearing? What is that?" or "That's a great dress!”. Once, someone in New York asked me "Are you wearing Yohji [Yamamoto]”. It's just so amazing that, when a sari is taken out of the rigid view we have of it, then it just really opens things up. Just knowing you don't have to use safety pins [can cause a] shift and you can do what you want with it.

Who is the sari for?

THE KINDCRAFT

I know you did a survey of where people's perceptions were starting from...

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

The survey, for us, was important — it was more like what's technically called a "dipstick study". It was done all in India because we wanted to understand it on the home ground first. When you say things like "most people don't know of various sari drapes", one can easily think we're talking about people outside of India and what was amazing to us is that this misconception stemmed very much from within India.

We felt this was the case, but we wanted to be a bit more sure. And just with the research that was done, it overwhelmingly — beyond the shadow of a doubt — confirms there's something there. In terms of perceptions held, in terms of the sari being held very dear to many people (whether they wear it or not), and in terms of — what I thought was interesting — in terms of Indians feeling like anyone could wear it.

That idea of cultural appropriation: It's a very western concept and a question that I only get asked by North American publications or media, or by people who ask "Can anyone wear a sari?”. In India there's an openness... I think Indians are generally open about culture. As long as it's treated with respect, then of course! We're happy for people to dance, sing, eat, and dress — but I think people really, when it comes to the sari, draw a hard line about that — especially with the whole "P.C." thing that's been really developed in North America, right?

THE KINDCRAFT

To that end—You've said elsewhere that you want to highlight how the sari can be a utilitarian, functional garment for modern urban life in India. Do you think the same could be true for other places like, say, New York?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

I mean.. why not! Dress and fashion — isn't that what it does? It pulls from different cultures, different parts of the world, at any given point and at all times, right? We see that in design every day — whether it's product design or fashion design, or architecture — and it's then adapted to fit the context. So, by all means, if someone feels that it's a solution that works for them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohIUYRtL0EE&feature=youtu.be

There's Stacy, who we know from Instagram; She lives in Chicago and, I don't think, has any familial connection to India — but she's an ardent wearer of the sari. There are people who have, for whatever personal reason, found comfort in the garment then and think about it as an incredibly classic, sustainable garment that makes sense for their daily living and wear it very often.

I think the world is increasingly becoming more fearful of this idea of "overstepping boundaries". We keep speaking about it becoming more inclusive but, when we look at what's happening across the world, it's like it's almost becoming more segregated. It would be a shame for things like this to just be cut out in slots, right? It's the same for food; Dress, food — they all go hand-in-hand, right?

Building "The Sari Series"

THE KINDCRAFT

How did you raise the money to do this?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

The total project budget has come out at 1.2 Crore [about USD$185,000]. We were about 10 percent over budget which, for a project we've never done before, I think is quite positive. What we've done on this project with this budget has been phenomenal and I'm so thankful for the people who worked on it and funded us — they were able to see it and believe in it for its bigger vision.

We've had incredible support from a handful of people, including over 400 backers on Kickstarter. We were very fortunate to have had Anita [Lal, the Founder/Creative Director of sustainable/luxury brand Good Earth] match Kickstarter, one-for-one. She then bridged the majority of the remaining raise and so Good Earth is now about a 65 percent funder of the project and they're the lead patron.

We've also had other friends and associate producers step forward as well and gave a few thousand dollars each, which bridged about 10 to 15 lakhs [USD$15,000—$23,000]. Raw Mango also supported us and Anuradha Mahindra of Verve Magazine stepped forward for the last 18 lakh [apx. USD$27,000] which we were over budget.

There's a lot of different things you learn along the way about how incredibly difficult fundraising is — and how every dollar counts: My [Kickstarter] bank account is Canadian, and a lot of people just assumed the campaign was raising funds in U.S. dollars — and so they ended up pledging almost 30 percent less than they wanted to due to the difference in exchange rates.

I'd also like to point out that some of the people we went to initially and who we really thought would be in a position to fund the project in its entirety — organizations like India's Ministry of Textiles, UNESCO, or the Tata Foundation — said "Great initiative and, in theory, we support it. However, not financially”. And the reason being is many groups define "impact projects" as on-the-ground initiatives within the crafts community. Digital is also still widely misunderstood and harder for many people to understand — especially when they're so used to working in a tactile, physical way.

My answer was always that this project is synonymous with impact: It's just the other side of a supply/demand conversation. And, of course, we're not able to quantify impact for our project — but there is something to be said for that other end of the equation: the consumer or the public.

THE KINDCRAFT

So people working with craft communities need to look at the demand side and not just the supply side?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

For certain and that's one of the things we've always worked towards at Border&Fall and our conversation with craft. I think it resonates with so many people is that it doesn't take the "death of craft" approach or, like I said, the "Save the Sari" approach... or using images of "hands on the loom". That side of the conversation is the status quo and, for us, it's "What is the other opportunity?”.

A new design language in India

THE KINDCRAFT

One of the things I really find so fascinating and wonderful about what Border&Fall does is that it doesn't shy away from the more nuanced — and sometimes the more difficult — conversations about doing new work which intersects tradition and examining the kinds of language and imagery we use in the process. Plugging this approach back into "The Sari Series": There probably aren't going to be a lot of "hands on the loom" photos, right?

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

With this project, we asked ourselves "What should look like?" and... we didn't know. I didn't want to be prescriptive of what it needed to look like. I wanted it to be something that was a synergy of a group of people coming together and that's very much what you'll see. There were many conversations about not appropriating Western imagery, which tends to happen all too often. We were like "How do we not fall into this?" and it's amazing... you can want to escape something so much and, at the end of the day [if you're not careful], you kind of feed into it.

And I think what ends up happening with all of us working there on the ground is our references are so similar and there's not enough happening in the design space in terms of developing their own language. I know that all the clients we work with are very much doing that and, when someone asks me "How is all your work connected?", I like to say that the ties that bind are really a group of people working to contribute and develop a new design language in India. That's still not specific enough and I'd love to be able to hone that a bit more, but whether it's Raw Mango or Rashmi Varma or Ruchika [Sachdeva] of Bodice — these are these are people who undoubtedly have their own stamp of looking at things through a different lens. They're adding something new to the conversation which is very much different from each other and, yet, still aligned in terms of their references and the integrity of their ideas.

You're speaking to the aesthetics of the project and, as it specifically relates to The Sari Series, it's very much the reason I approached Bon Duke in the first place. He's a New York based filmmaker — first generation Vietnamese, born and raised in Brooklyn, whose work I've liked for many years. I wanted to work with him because we need to push the definition of what the visuals stand for. I reached out and sent him an email; He wrote back and, when I met him, he just so clearly understood the opportunity and was on board — which was incredible to have that understanding and validation for someone who had no connection to the sari and had never been to India.

THE KINDCRAFT

It has to be a very different kind of project for a creative agency to not be working for a brand, but to take on a garment for a client.

MALIKA VERMA KASHYAP

If it was a client, I'd say it's a client with multiple personalities. [LAUGHS]

Usually our work involves trying to understand the real DNA of a client and then bringing out a singular voice and vision. And so using that analogy — which I think is interesting — as a client, it would definitely be one we keep learning from. It's not about boxing it in and finding the singular way to say it.

And that's the beauty of the sari — that it's not singular. It is so incredibly versatile and dynamic. It is a million things. It is a textile, it is culture, a history, a memory, it's love. It's just... I don't know what it isn't. And that's what's so incredible about it.