Having walked from the Bedford Avenue subway stop in Williamburg, Brooklyn to a quiet street in Greenpoint, I found the unmarked door that I was looking for. Stepping off the concrete sidewalk, I passed through an alley garden, climbed a flight of stairs, and arrived at the entrance of Sri Threads gallery featuring Japanese boro textiles. The door was held open for me by its founder, Stephen Szczepanek.

As I entered, I was awestruck by the large loft space with high ceilings where a kimono soared above wooden tables neatly piled with soft textiles.

Once the curator for a private art collection in New York City, Szczepanek started Sri Threads in 2001 to showcase items that he collected on his trips to China, India, and Japan. It’s not just the textiles that Stephen collected over the years, it’s the stories behind how they were made and used. As he showed me one rare item after another – noting the age, origin, technique, and material of each piece - I felt as if he was introducing me to the village elders themselves. I imagined the women who carefully wove and stitched these pieces together in a village setting long ago.

Perhaps it was the combination of storytelling with the softness of the vintage textiles which gives a visit to Sri Threads such an unmistakable feeling of coziness, as if you've stepped into a different time and place. Each of the handwoven items on display seemed to hold the spirit of the person who made and wore it. Each boro patchwork piece – having been mended and stitched, again and again – has come to possess a remarkable soft beauty and a distinctive character.

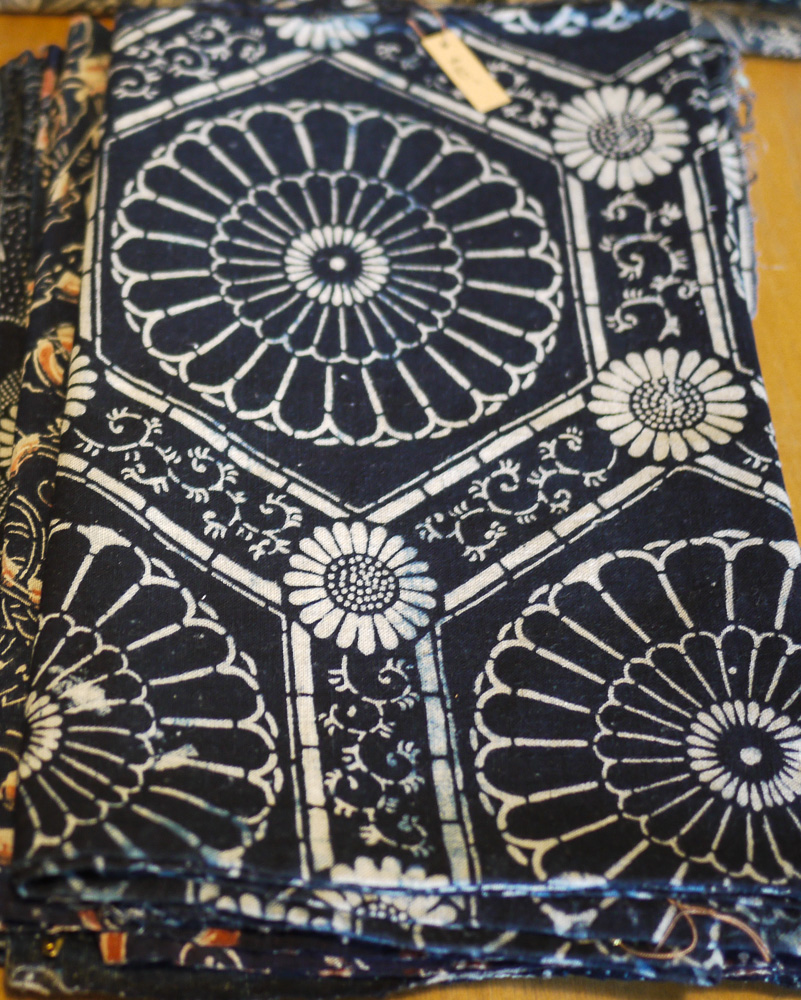

Japanese Indigo

Stephen has an impressive collection of resist-dyed indigo textiles. Techniques range from shibori (shape resist dyeing and tie dye) to katazome (paper stencil rice flour paste resist dye) and tsutsugaki (resist dye freehand tube drawing).

There were also examples of sashiko (running stitch quilting) and weaving techniques like kasuri (ikat weaving) and sakiori (rag weft weaving, with a bast fiber or cotton warp). I was particularly interested in the asa (bast fiber), items made of hand-plied hemp or ramie that were used before the widespread use of cotton.

Szczepanek explained to me that, at the beginning Japanese cotton cultivation in the 16th century, cotton was too expensive for the farmers to use for their own clothing. Instead, they would spin linen-like bast fibers like hemp, ramie, wisteria, nettle and other foraged or cultivated indigenous fibers.

By the mid-eighteenth century, hand-loomed and hand-dyed cotton indigo cloth had become popular in Japanese cities among the wealthy – but cotton only became accessible to Japanese peasants in the early-to-mid nineteenth century.

To learn more about sukumo Japanese indigo farming and dyeing, read The Kindcraft's Maker Profile: Buaisou, Japanese Indigo Dyeing based in Tokushima Prefecture, which was once the heart of indigo production in Japan.

Boro Textiles

Boro is the Japanese word meaning “tattered” and refers to the humble, patched together and mended textiles and clothing once worn by peasants. These utilitarian clothes were generally made of nineteenth and early twentieth century hand-loomed indigo dyed cotton scraps or cloth woven from bast fibers because cotton yardage wasn’t widely available to countryfolk until the early-to-mid nineteenth century.

Using these scraps, women made patchwork clothes. They then mended them as they aged, creating layer after layer, which had the added benefit of extra warmth.

Before boro textiles, there were kesa, which were the patched together garments worn by Buddhist monks as the outward expression of the Buddhist ideal of poverty.

Stephen has a special interest in antique boro textiles and has been collecting them in twice annual trips to Japan over many years. He noted that because most aspects of traditional life in Japan essentially ended at the start of WWII, folk textiles are increasingly difficult to find in modern Japan. When he is able to find them, he chooses textiles based on their rarity, strength of character, and aesthetic appeal.

It’s quite possible that Sri Threads is home to more Japanese vintage textiles than can be found in any one collection in Japan. Szczepanek often lends portions of his extensive collection to museums, and was recently a contributor to an exhibition of the Domaine de Boisbuchet / C.I.R.E.C.A., France in cooperation with the Museum of East Asian Art, Cologne, Germany.

At home in Brooklyn, Stephen’s clients are mainly designers and fashion professionals. With the current trend of indigo dye and the patched-and-stitched denim repair, Sri Threads has plenty of inspirational material.