There’s no English word for Morrison Polkinghorne’s chosen craft. When the Sydney-native first started making tassels, bullion fringing, and ornamental rope – a pursuit known collectively in French and Italian as passementerie – he was the only such artisan in Australia to employ purely handmade techniques.

In between commissions for heritage homes, heirloom restorations and contemporary interiors under his label Passementeries, Morrison travelled back and forth to Myanmar and other parts of Asia, drawing inspiration from the materials and techniques he encountered. In 2014 he relocated to Southeast Asia permanently, choosing Battambang in northwestern Cambodia as the site for Bric-a-Brac, his studio-cum-retailer and boutique hotel.

One sunny Sydney morning in 1991, Morrison Polkinghorne received a fax from London. The inky pages that emerged from the machine that day had recently been unearthed by an acquaintance who was working on the restoration of Windsor Castle. They revealed a diagram of an 18th century French passementerie loom: a piece of specialty equipment used to weave bullion fringe, an elaborate decorative trimming used on curtains and cushions.

Over the course of a weekend, with nothing but the diagram to go off, Morrison built a timber replica loom and began teaching himself how to weave. The elegant mechanism, which uses a wheel attached to an adjacent wall to feed six spools of twisted thread or rope into the warp, is still in action today, set up on the rooftop of Bric-a-Brac overlooking the sleepy streets of Battambang.

Once a colonial outpost and now a creative city that’s home to Cambodia’s highest number of artists per capita, Battambang fuses old-world charm with contemporary creativity. It might just be the perfect place to revive passementerie. Bric-a-Brac occupies a grand four-story corner building in the centre of town. The shop floor that opens onto the pavement is reminiscent of a Parisian boutique, which is where Morrison first fell in love with passementerie while travelling around France in 1990. After building that first loom a year later, he made the decision to transition away from a successful soft furnishings and upholstery business and dedicate himself to tassels and trimmings.

Much of Morrison’s early work for Passementeries came from replicating discontinued trimmings for private clients. He diligently recreated 18th century French designs and found inspiration in fabric house Scalamandré (in time they came to represent his work in the US). He created custom fit-outs for some of Australia’s premier heritage buildings, including the Prime Minister’s residence at Kirribilli House, and a private commission for the Packer family.

Reminders of that period can still be found lying around Bric-a-Brac – in the boxes of 120-year-old Irish linen that Morrison found at a Sydney market and carted all the way to Cambodia. Most of the other materials he uses – including gnarly jute, un-gummed silk and mercerised cotton – are all sourced across the border in Bangkok. Morrison has accumulated a color library of more than 600 thread hues.

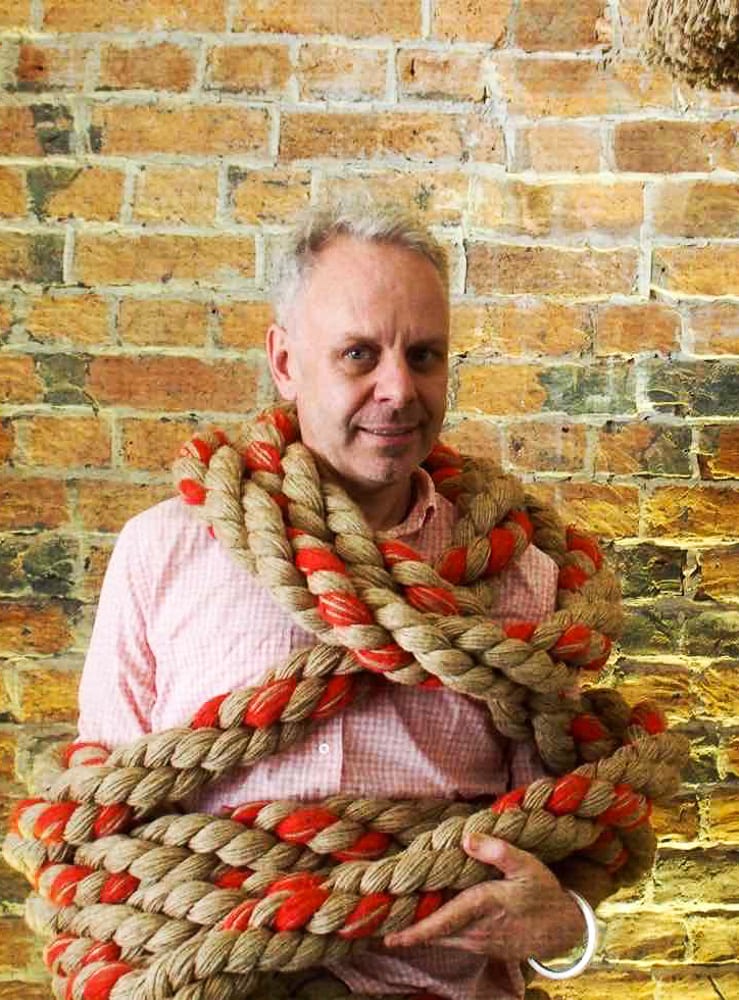

His latest creations range from micro tassels fixed to the ends of pencils and delicate Turk’s head shirt buttons, to a massive 20-kilogram rope – part of a series commissioned for Sharky’s Restaurant & Deli in Yangon. Most objects are ornamental and purely decorative, but other designs, like Holland blind tassels, also have a functional use (tassels were originally invented as a practical way to finish the end of a rope).

Like jungle vines, tangles of rope, tassels and ornate braiding dress every corner of Bric-a-Brac – some original designs, others antique pieces. In the beginning, the space was supposed to be a studio but as the retail side of Morrison’s project took over and he started adding local labels such as Penh Lenh to his offerings, most of his equipment moved upstairs. A single 12-heddle loom and workbench are still set against the shop’s front window.

As he runs through the anatomy of a tassel, Morrison highlights the combination of hard and soft elements. Head and body are created by wrapping, binding and netting threads over a timber or metal mould – or sometimes the mold is left exposed. A cord relief element and super-fine, velvet cut ruff can be added before the transition to a bullion skirt (thick fringing). Some of Morrison’s designs incorporate Burmese lacquerware and hand-turned wooden moulds; others use locally made beads or foraged seed pods. Some tassels end up being attached to woven braiding trim, itself a highly textured, three-dimensional panel of layered threads.

Preferring to call himself an artisan rather than a craftsman, Morrison practices a combination of time-honoured techniques and methods invented out of necessity. He recently developed his own system for cutting perfectly proportioned, tiny pompoms; but he also uses a range of knots learned decades ago during his days as a boy scout. He once saw a sketch of a rope wheel designed by Leonardo Da Vinci in a book, then copied it and built his own (with the addition of a 240-volt motor to speed up the rope-making process).

For the most part though, passementerie is extremely time and resource-intensive. One meter of braiding takes about 20 minutes to finish, while twisted rope requires up to 30 meters of raw material to yield just 10 metres of product. Two people working full-time over the course of a day can produce between six and ten meters of bullion fringing.

Morrison needs help to keep up with his orders, and on this front he has found Cambodia to be a surprisingly advantageous work environment. Channa (pictured above) is one in a small team of Khmer staff who now work at Bric-a-Brac. Believing it’s much easier to teach passementerie to people who have no background in textiles, Morrison has found that local staff are both quick to learn and dexterous. Tassel heads forged by a local metalsmith have made their way into many of his recent tassels, and Battambang’s abundance of skilled machinists have come in handy for repairing or modifying his homemade equipment.

Although he doesn’t draw specific influence from Cambodia’s textile traditions, which he laments have all but disappeared in this part of the country, Morrison still travels compulsively in search of new materials in techniques. His latest obsessions are basket weaving – which he tried his hand at in Northeastern Thailand - Malaysian ikat, matmee, lotus silk from Myanmar, and a method for making Korean blinds that he saw demonstrated in Seoul. When you are completely self-taught and as talented as Morrison, the options seem endless.