The color known as "Japan Blue" has taken the world by storm. Today we see examples of shibori resist-dyed materials as everything from cushion covers to apparel, highlighting the trend towards all things indigo-dyed.

But indigo is not new. Humans have used this tropical plant to dye cloth pale shades of blue like the sky to inky navy since the days of Egyptian mummies. Natural dyes like indigo and hand-woven textiles have long been a heritage craft in indigenous cultures from the Americas, to Africa, and Asia. Anthropologists recently uncovered the oldest known indigo-dyed fabric in Peru's Andes Mountains dating back an astonishing 6,000 years. In Japan, indigo-dyed - or ai-zome - textiles can be traced to the 8th century, but peak-production of indigo farming and dyeing was in the Edo period between 1600 and 1868.

Today's ultra-modern Japan doesn't produce traditional arts anywhere near its pre-war levels, but there are groups reviving these crafts, and a few dye houses remain from the Edo era. We visited the 200 year-old Higeta Indigo House in Mashiko, Japan on a recent trip to the island nation, and stopped by Tokyo's Amuse Museum to see their boro patchwork textiles.

Higeta Indigo House

Under a traditional thatched roof supported by joined timber beams sits 72 Japanese indigo vats. The Higeta Indigo House in Mashiko, Japan's Tochiji prefecture dates back to the mid 1800's and has practiced the art of indigo and vegetable dyeing for the last two centuries. The Higeta house is one of the few remaining Edo-era dye houses to engage in indigo dye production, cotton cultivation, yarn making, yarn dyeing, and hand-weaving.

Indigo dye is made through a long and delicate a process of fermentation using indigo leaves - or sukumo - wheat bran, hardwood ash, lime, and sake. Among the vats are vents where straw and wood burns in cool weather to keep the temperature of the indigo dye between 25 and 30 degrees Celsius, depending on the stage of fermentation. Of the 72 vats, the Higeta family makes about 30 different shades of blue indigo dye.

The dry-leaf process that Japanese indigo dyers use is different to the processes in India or Thailand. To learn about the step-by-step process from plant to paste in Thailand, read our story here.

Master craftsman Tadashi Higeta is a 9th generation indigo dyer and weaver. He and his family live on the property and create dye from the Polygonum Tinctorium plant - as well as growing, spinning, dyeing, and weaving the cotton that they use in their textiles, a process known as ito-zome.

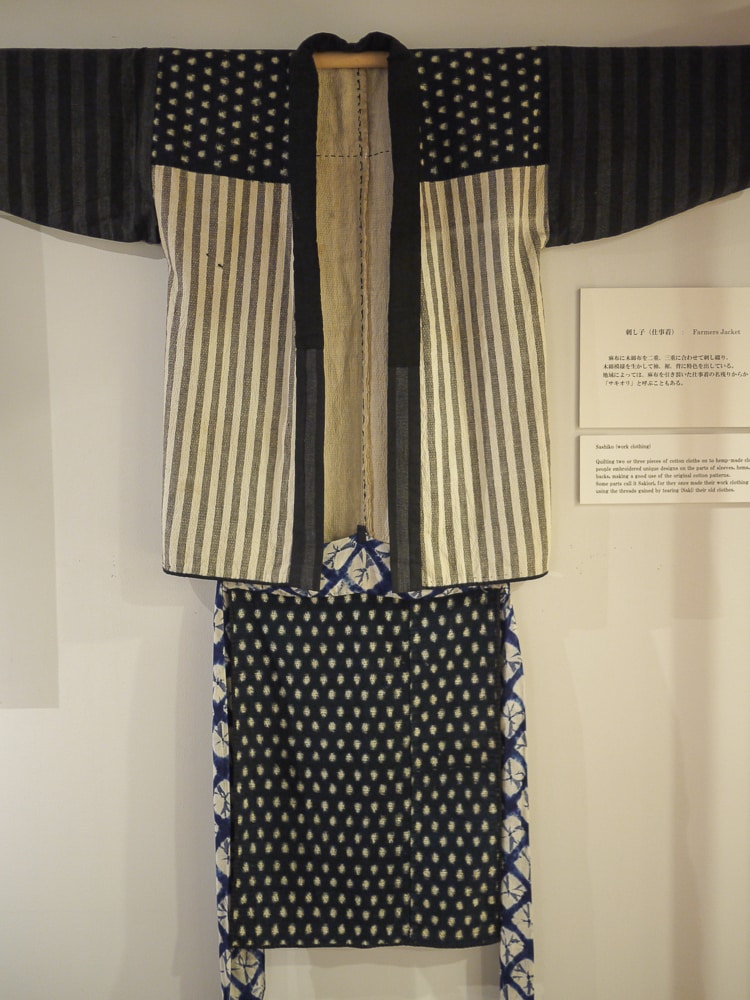

They also use various traditional methods of decoration: the well-known tie dye-like technique called shibori-zome or shibori, and the kata-zome stencil resist dyeing. The stencils are made from Japanese washi paper - coated with persimmon juice for strength - and are brushed with rice paste then dipped into the indigo vat. The rice paste is later washed off with ash lye and the pattern remains on the cloth.

The 'Boro' Textiles Exhibition

Located in Asakusa, Tokyo near the famous Sensō-ji Buddhist temple, the Amuse Museum specializes in Japanese indigo-dyed textiles and ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings popular in the Edo era. During my visit, there was an exhibition called 'Boro', which featured antique patchwork textiles and apparel.

A large part of the museum features the personal collection of ethnologist and author Chuzaburo Tanaka. Born in the Aomori prefecture in northern Japan in 1933, Tanaka gathered upwards of 30,000 pieces of Japanese folk art over his lifetime. Descriptions of most pieces are available in English at this private museum. Tanaka's narrative about his journey - and the people of Aomori who made and wore the items in his collection - offers a heart-felt perspective on life in ancient times and the significance of these heritage textiles.

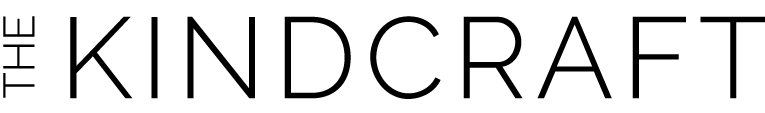

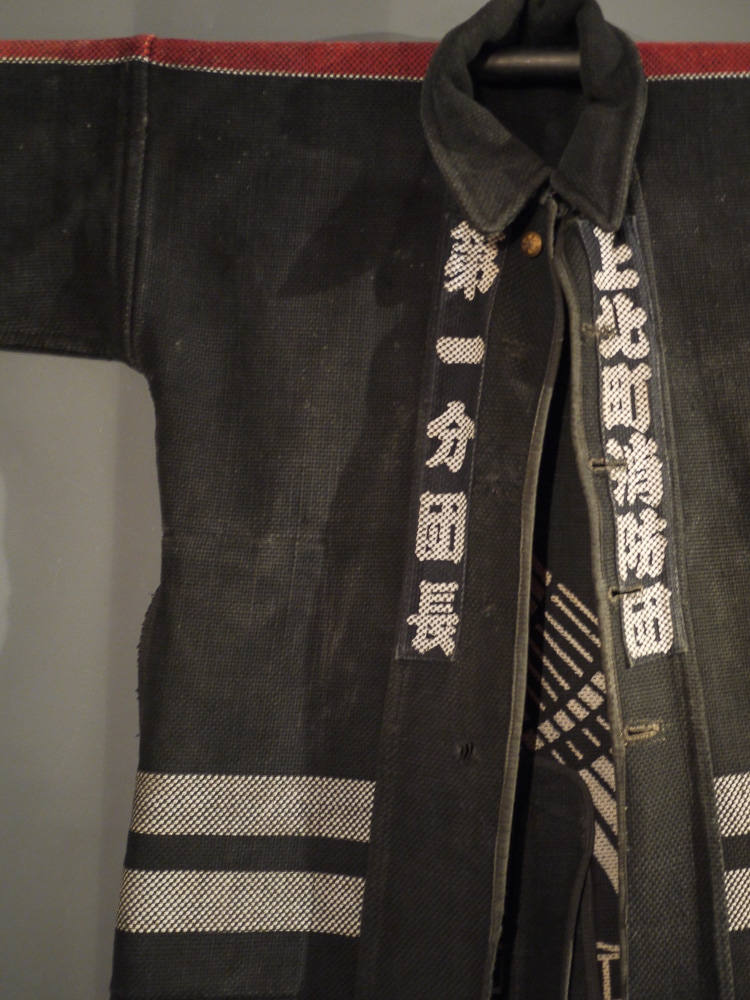

In addition to boro patchwork, there were several other techniques on exhibition: shibori resist-dye, kata-zome stencil prints, and sashiko stitching - a quilting technique using running stitches to decorate and give strength to one or more layers of fabric. Sashiko garments were hand-stitched by commoners who needed warm and sturdy utilitarian clothes in the cold northern regions of Japan.

Any scrap of hand-loomed indigo-dyed cotton or baste fiber, like hemp or ramie, that a rural person could get their hands on was used to create apparel for practical purposes. The word boro means ragged, or patched and mended, and was used as workwear for farmers and fisherman. These garments were the focus of the Amuse Museum's 'Boro' exhibit, a word that is known around the world today.