When Paola Antonelli needed a username for Twitter, she chose "Curious Octopus" — a fitting sobriquet as someone known for "reaching into and grabbing from a wide spectrum of disciplines, from design to architecture to science to technology."

Antonelli's hands continue to be at work in many places: Not only is she the Museum of Modern Art's Senior Curator of Architecture & Design and its Director of Research and Development, but the curator of the XXII Triennale di Milano ("Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival") and also the host of "&Design", a streaming series which examines design’s interaction with — and impact upon — human experiences.

THE KINDCRAFT sat down with Paola Antonelli at the 2018 Jaipur Literary Festival, where she appeared on its "Fashion and Modernity" panel (along with Border&Fall's Malika Verma Kashyap). We started our conversation by asking about MoMA's recent "Items: Is Fashion Modern?" exhibition but, before we knew it, the curious octopus took hold and pulled us further into the depths of design, technology, and craft.

THE KINDCRAFT

Do you mind talking about the exhibition that just closed, "Items: Is Fashion Modern?"?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

I do it all the time — to talk about exhibitions and what I learned from them. I mean — that's the best part of it, in my opinion.

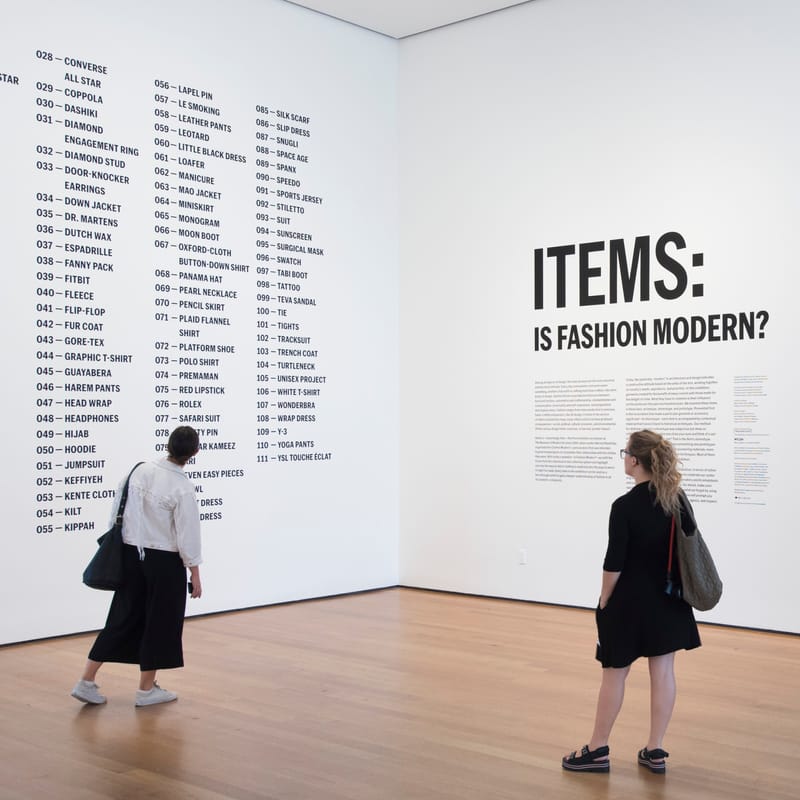

You do an exhibition and, traditionally, you present the audience with the work or the canon. And that's not how I like to do shows. I learned it a few years ago with an exhibition called "Design and The Elastic Mind" that was about design and science that, sometimes, if you leave the questions open-ended, the audience fills in the dots and you get to learn a lot — and they become almost generous because they are involved in it, so it becomes much more fun for everyone.

And the same was true with "Items": Just having the list made everybody immediately feel involved. Then we had a lot of programs during the exhibition that were about participation, but not in the old-fashioned, trite meaning of the term.

First of all, we asked people to nominate the 112 [items in the exhibit], right? We gave a hashtag they could use on social media to let us know. Secondly, even if we didn't ask them they would tell us anyway [LAUGHS]. Thirdly, we had a MOOC called "Fashion as Design" on the Coursera platform. Many people took the course and, actually, somebody came to me today saying "I took the course!".

We also had programs of all kinds: We had a beautiful program that was about the unsung heroes of fashion — everybody from the licensing expert to the lawyer that deals with copyrights to the person that sources cotton. It was about showing the whole lifecycle.

THE KINDCRAFT

Is there anything specifically that you learned from the exhibition?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

I learned so much! First of all, I'm not a fashion expert, so it was a crash course. I mean — I'm from Milan so, as a teenager, I worked in fashion. It's an industry town...

THE KINDCRAFT

You started at Armani, right?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Yeah — I was 15 and keeping the press separate from the buyers at fashion shows while working as an intern at Armani's PR office. I knew fashion — but not as a scholar, so I had to do a crash course. That's one of the reasons why I came to India about a year and a half ago; I was learning not only about saris, Kashmiri shawls, and salwar kameez, but also about the making of objects — the textiles and everything else.

THE KINDCRAFT

With fashion, are you design and materials-focused — or more interested in the technology?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Technology and materials and crafts are the same thing.

THE KINDCRAFT

Explain that to me.

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Whether you use your hands or use a machine, it's still something we're doing. I mean — once artificial intelligence is designing, maybe it'll be different. But I don't see any difference naturally.

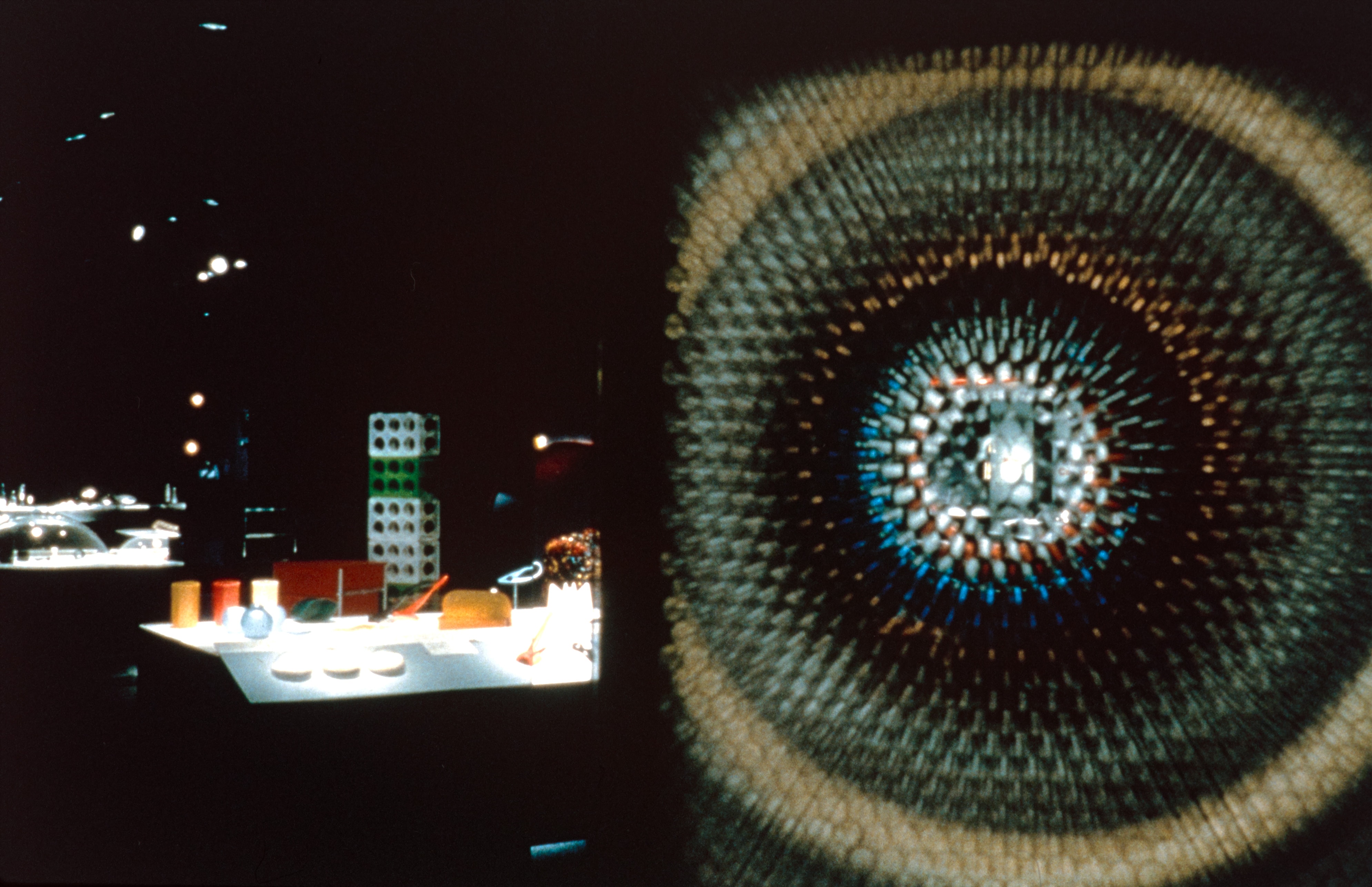

My very first show at MOMA was called "Mutant Materials in Contemporary Design". It was 1995. At that time I realized that the more advanced the technology, the more you need crafts because there's no machines to work these new materials yet... so you need to know how to work them by hand. And, you know, the most advanced fibers and composites were all laid by hand, right? So making a distinction between technology and crafts is a false notion — and it creates a divide in our society that's a little bit dangerous.

Technology is separate from craft in that many of the people who work in technology think they're not interested in craft. That's a real problem, but it's changing now that more and more designers are getting hired by high tech companies.

If you think of Modern Meadow, for instance, which is the company that created this liquid leather called Zoa. Andras [Forgacs], the founder, is the son of a scientist; He was able to work on the scientific revolution but, as soon as he could, he hired Suzanne Lee who's a designer. There are people like Andras that realize the need for designers, that know to both understand technology and to work with their hands.

THE KINDCRAFT

What about the reverse? Designers reaching back to traditional making techniques or crafts?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

There are many, many, many. I think it's fundamental.

I have several examples: One is Formafantasma -- They're two wonderful Italian designers working in Amsterdam and their work is fantastic. At some point, they did a project in which they recuperated pre oil-era resins and they started seeing how to do things with honey, beeswax, and straw. Or there's Satyendra Pakhalé, who was a designer for a car company and studied product design; He does contemporary work [in Amsterdam] but, once a year, he comes for three months or three weeks, depending, and studies a lost wax process in the part of India where he's from and then he applies it into all of the high-tech objects.

THE KINDCRAFT

So you think distinctions between technology and craft are artificial?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Absolutely.

THE KINDCRAFT

This might be an interesting bridge to talk about your curation of the upcoming Triennale di Milano, which is called "Broken Nature". With fashion now, there's a greater awareness of the environmental impact of the industry and, more broadly, about consumption...

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Oh my god, yes!

THE KINDCRAFT

Is some of what you learned from the "Items" show driving choices you're making for "Broken Nature"?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Always. Everything that I've done in the past drives my choices now.

The idea of "a broken nature"... It's multipronged and I'm still working on it, but you were talking about consumption. For instance, I've eliminated the words "consumption" and "consumers" from the way I speak because I believe in changing mindsets. If people stop thinking of themselves as consumers and instead think of themselves as citizens, people, humans, then maybe they'll have a different attitude towards things. I believe strongly in that.

Another change of attitude that's happening — and that goes to the idea of consumption and broken nature — is repairing. You know, there are so many cultures in the world that have lost the idea of repairing, but there are so many "repair bars" that are happening everywhere -- which is a little hipster-like and Millennial... but it doesn't matter. Whatever it takes, right? [SMILES] I live at Canal and Broadway in New York and, when things break, there are Senegalese people there that know how to fix them. I go and I give them the object. They fix it and I pay them. You know what I'm saying? We need to go back to that way of thinking.

THE KINDCRAFT

Is a distinction between "repair cultures" and "replace cultures" apparent to you as you travel globally?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Absolutely. And you know people should stop using "developing country" and "developed country", because I don't know who's more developed. It's like "the developed countries" are the countries where people know how to fix things, as far as I'm concerned, and don't throw them in the street if they don't work anymore.

It really is fascinating. There's a divide in the world that is certainly about economic growth and developed economy, but it's also a divide that is about wisdom. And it goes in reverse.

THE KINDCRAFT

Is your job to communicate ideas like this to people who may not be familiar with them?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

My job, as far as I see it, is to help people develop their own critical tools. And I give them both the self-assuredness and also the notions that they need for that to happen. If I expose them to a world where people repair their socks and repair their microwaves, they might think twice before they put it in the streets. Maybe they don't even know that that's possible?

THE KINDCRAFT

How do you do that?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

You just let them know. People absorb like sponges — in a second. It's amazing how receptive they are and perceptive and reactive when you give them ideas that might be eureka moments for them, like, "Oh, my god —Can you really repair a microwave?" When I grew up in Italy, there were stores where you took things to get fixed. In New York, it doesn't exist. I don't know anywhere in the United States where you know how to get anything fixed.

THE KINDCRAFT

How does presenting ideas and letting people "fill in the dots" relate to your role doing MoMA's R&D? And how do you envision using tech to do that?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

First of all, R&D is not about technology. I call it "R&D" because it's the strange dissonance between a cultural institution and a corporation. And I also always say that I make a lot of "R" and very little "D". The idea behind the R&D project is that I believe museums can be the R&D of society.

THE KINDCRAFT

But not to apply technology?

PAOLA ANTONELLI

No — R&D in the sense of doing research and developing ideas.

R&D is about taking really serious topics — like death, like the future, like truth — and having these discussions with experts that highlight the museum as a place where you can have serious discussion, number one. Number two: how art can help you deal with death, the future, etc. And number three, how the museum can help you also deal with them. But that doesn't mean that I haven't been involved in the technological side of MoMA since the beginning, because I coded the first website.

Technology, once again, is part of our life. And the problem is that too many people think it is not, so they say "Oh my god! Technology: Is it going to ruin museums?" No.

The most important thing is to accept technology as part of our lives and, therefore, use it in the right way as opposed to being overwhelmed by it. You know—it's not an alien body that you apply or you call on when needed. Technology is very helpful for museums — not virtual reality. Actually VR is terrible for museums because people would bump into the art.

But augmented reality could be [helpful].... Websites certainly are, social media is. There's a lot of technological advancements that are extremely important. Some are on the front end and some on the backend: Artificial intelligence could help us have more viable and searchable archives.

There's a lot of possibilities but, definitely, I'm all for technology. [SMILES]

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.