In the mornings—when the thin air of El Alto, Bolivia is especially cold—Aymara and Quechua street vendors in the world's highest metropolis leave their homes and make a short trip to the neighboring capital city of La Paz. Many sell their wares on a bustling tourist street called Calle Sagárnaga, a crossroads for Bolivians and foreign visitors for hundreds of years. And so, perhaps, it's not a surprise that a chance meeting on Calle Sagárnaga paved the way for Andi'Art—a project combining the talents of Bolivian textile weavers and a French designer.

Andi'Art's origins reach back to 1993 when Véronique Valdès first arrived in Bolivia with her husband. The couple had been living the life of slow-traveling nomads, exploring South America in search of the right place to settle down with their two-year-old son and, eventually, choosing La Paz as their new home.

Always interested in materials and processes, Valdès began learning about Bolivian traditional weavings like the Jatan Aku, a traditional, multi-purpose textile made from alpaca or llama wool. When not used as rugs in mud houses or as blankets during the freezing nights in the Andean High Plateau, farmers use Jatan Aku in the potato fields as carrying bags. Though functional, each weave is also purposefully designed in specific combinations of colors and patterns.

“Before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century," said Valdès, "each family had its own design styles. In the absence of a writing system, these patterns were the ID cards of pre-Columbian Bolivia."

Indigenous people used a great diversity of native plants, minerals, or insects to dye the llama and alpaca yarn into their distinctive colors which helped them to identify which bag belonged to whom during the communal harvests. Some textiles were decorated with anthropomorphic characters, symbolizing indigenous religious beliefs—but these motifs were banned by the Spaniards for two centuries and nearly disappeared.

"Today, these rugs are very rare and hard to find,” she said.

Starting the Business

Valdès returned to live in France in 1999 but, after deciding to start a business to restore and sell Bolivian textiles in Europe, she returned to Calle Sagárnaga in 2000 to acquire her initial stock.

She bought a few Jatan Aku rugs from a middle-aged Quechua street vendor named Bonifacia, a woman with whom she felt an instant rapport. Deciding to partner with Bonifacia, Valdès restored and sold these rugs in Europe—sometimes transforming them into things like cushion and sofa covers. Her striking creations were first introduced to the European market when they caught the eye of French interior design shop Caravane.

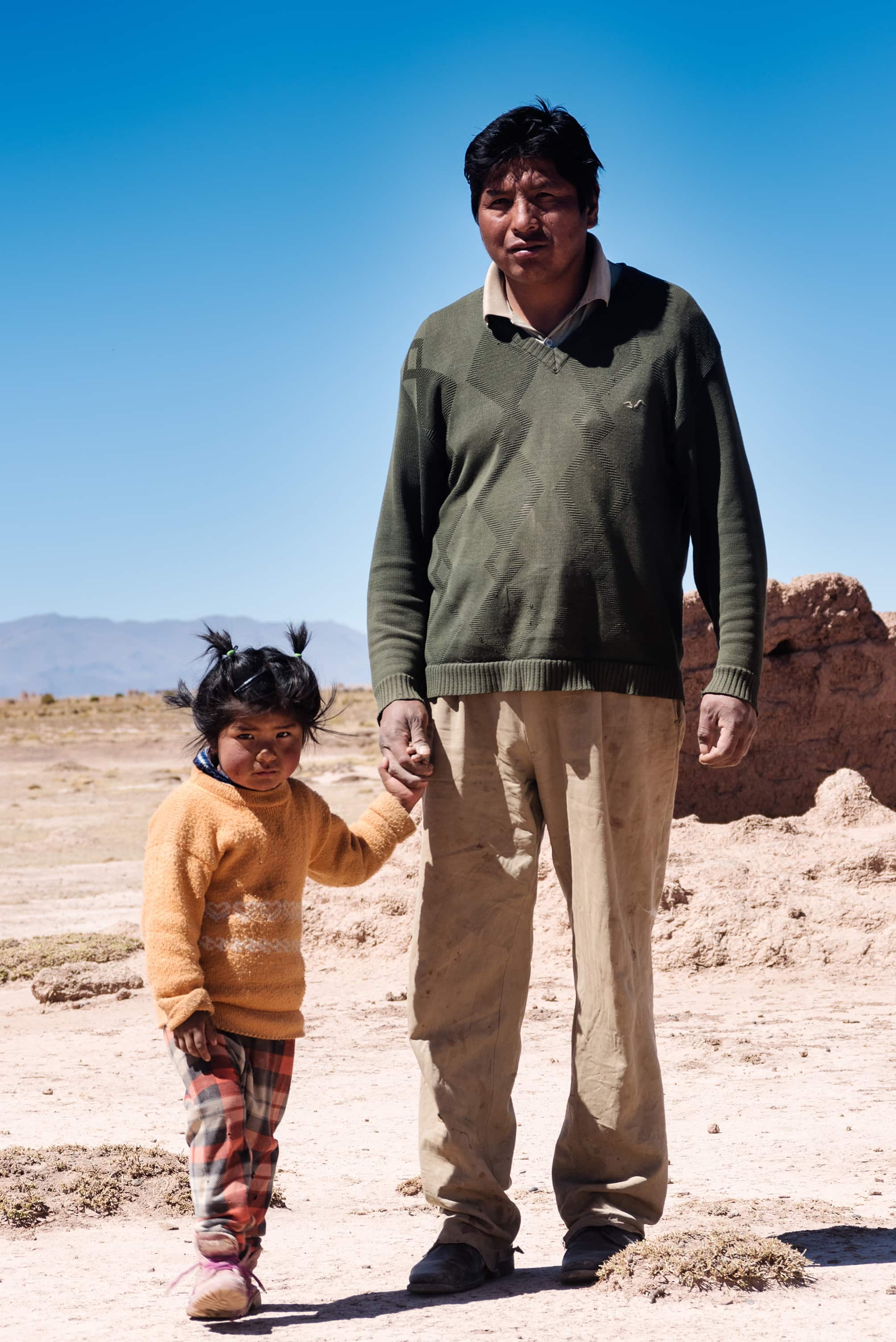

Bonifacia passed away in 2002, but her daughter, Nieves, took over her mother's work—and even brought her own children into the business.

"It's really a family affair," said Valdès. "I've taught Nieves's daughter, Monica, basic needlework and knitting, textile restoration and natural dyeing. Nieves is an experienced weaver and has trained her two sons. The two of them weave most parts of the collection. Nieves has become an efficient production manager and a dear friend. She buys wool at the El Alto market and she manages the whole production process."

It wasn't always such a smooth-running operation: Valdès said that, at first, her requirements were misunderstood—or bluntly rejected—by the indigenous artisans. "A plain alpaca white rug was an unheard-of style, something unfathomable. Nieves said it would never sell."

Valdès said it took five years to achieve a micro production of white alpaca rugs—and an additional 5 years to reach the current quantity in production. "For years I could not get the rugs I had ordered, but I never refused a single piece because I didn't want to offend the weavers. I just kept explaining over and over what I actually wanted. You cannot give orders to the indigenous weavers. You must be patient and convince them they can do something they have never done before."

That patience has paid off: Andi’Art’s colorful rugs and pillows are now exhibited at MAISON&OBJET Paris and sold in places like ABC Carpet & Home in New York and Le Club 55’s boutique in Saint-Tropez.

Sourcing the Fiber

Every Andi'Art creation starts in El Alto with the purchase of sheep wool or camelid fibers (primarily llamas and alpaca) sourced from Mercado 16 de Julio, the city’s huge, open-air market. Wool fiber is sold in 400 gram balls of 1-ply yarn or directly from raw fleeces weighing up to 6 kilograms, all of which is carefully displayed on the ground to prospective buyers.

“We buy wool from over thirty different wool producers since gathering the right quantity and color shades can take some time,” said Valdès. Large wool growers typically sell their production to large textile manufactures, so Andi’Art works with small-scale farmers who raise herds of about 80 llamas— and sometimes even less. “We may buy 10 kilograms or 3 kilograms, depending on what we can find.”

The sheep wool used by Andi’Art is naturally coarse. It has fewer natural colors than camelid hair, although Merino sheep raised in Southern Bolivia in the Sucre region produce a high-quality fine-wool fleece.

Alpaca fiber is soft, light, tough, and warm. It’s also known for its unique elasticity and hygroscopic properties, as well as its wide range of natural colors, ranging from white to black including multiple nuances of beiges, camels, browns and exclusive greys. Baby alpaca is the finest quality, usually obtained from the animal’s first shearing or from an adult animal with a very fine coat.

“In Bolivia,” said Valdès, “alpaca wool is typically un-carded because the fiber has a natural sheen and inherent softness, but it is handspun with the Andean drop spindle (called the 'pushka'). Women spin all day long, throughout their lives, while walking to the fields or watching over their flocks.”

Llama fiber is more popular—but also more rigid and heavier. Each part of the llama body produces a different type of fiber: the legs and lower parts of the body yield a rough fiber perfect for weaving rugs. The “saddle area” yields a softer—and longer—fiber used to make sweaters and knitted hats. Llamas can live between 15 to 20 years, but their fiber becomes stronger and feels less soft over the years.

“The llama is such an integral part of Andean life that even the smallest farming families own at least one or two llamas,” said Valdès. “It’s like having a pet!”

The rarest and finest wool comes from the vicuña, a small and delicate camelid roaming wild in nature reserves in the high Andean Plateaus. The soft and warm fleece produces a creamy white to light brown fiber that, because the animal can only be shorn every three years, is reserved to make luxury goods.

Developing the Andi'Art Process

Once the standard single-ply yarn balls have been purchased, the yarn needs to be plied into 2-ply or 3-ply yarn to achieve the desired weight for rug weaving. Plying requires great hand skills as it provides strength and evenness to the yarn and, therefore, determines the quality of the fabric.

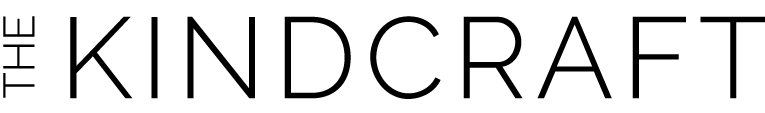

Nieves, the studio manager, works from home with her two sons or can outsource spinning and plying work to several families in El Alto. Whether in the semi-urban El Alto area or in villages farther away on the Altiplano, artisans traditionally work from home. They work at their own pace, often in addition to their daily farm chores, so they can maintain their family unity. Valdès said she’s accustomed to this small-scale, decentralized manufacturing process and is more focused on designing and making deadline deliveries rather than meddling with the production schedule.

Like most Andean textiles, Andi'Art textiles are warp-faced weaves: The warp is made of soft alpaca yarn and the weft is made with a more resistant merino yarn, or with a blend of alpaca and merino yarn.

Early Andi'Art rugs were handwoven on traditional Andean backstrap looms or on four-post looms which have the warp wound between two warp bars. Using this method, weavers had to work full time for three weeks to complete a one-and-a-half square meter rug (about 16 square feet). The difficulty of maintaining a production schedule was compounded by the daily routine of weavers who, traditionally, worked at night after farming all day in their fields.

Bolivia's extreme climate conditions also presented production challenges. "During the dry season," said Valdès, "we had to cope with wool shortage because of the drought conditions. When the animals can't graze and nourish themselves, they don’t produce enough wool. Some years before that, the yarn was rotting on the Altiplano during the wet season because of extreme rainfall and floods.”

To increase the scale of production, Valdès decided to transfer backstrap loom techniques onto a European-style treadle loom that is able to withstand the weight of long wool rolls.

It can take Andi'Art's weavers a full week to turn 7 kilograms of wool (a little over 15 pounds) into fabric rolls that are seven meters long and 75 centimeters across (about 23 feet long and nearly two-and-a-half feet wide). When completed, the rolls are then sometimes resized to fit specific orders, cut or joined together depending upon the final product.

The Final Product

Andi'Art owes its growing following to its fine natural alpaca rugs, but Valdès said she measures the project’s success in terms beyond sales.

“When we met Nieves and her husband, they lived in one-bedroom home with their six children. Today, they live in a big house, every kid has their own bedroom, and some of them went to college in La Paz. One became a fine-arts teacher, my goddaughter is a primary school teacher and Monica works in my studio in La Paz. Their living conditions have improved dramatically in just a few years”.

The successful collaboration has not only created a strong business, but a strong bond between two women — a relationship of deep, mutual trust which has used a cross-cultural exchange of ideas to flourish.