Encountering traditional Peruvian textiles can be an intense experience. Their vibrant colors and striking designs give us a glimpse into the myths and arts of ancient Peru — and into an era when all textiles were imbued with meaning.

Expanding on our earlier report about Peru's Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco, contributor Anne-Laure Camilleri takes a longer look at the center and its founder, Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez, exclusively for THE KINDCRAFT.

During the mighty Inca empire, feathered cloaks and fine handwoven fabrics displayed wealth and status. Textiles were so integral to their political, social and ritual life, in fact, that Inca rulers established textile centers to sustain the weaving of these beautiful cloths. The enigmatic appeal of Andean textiles has lived on through the centuries: Pre-Columbian weavings are known to have influenced 20th century Bauhaus artists such as Paul Klee, Josef and Anni Albers, and American textile artist Sheila Hicks.

Located in the heart of Cusco, the capital city of the Inca empire, the Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco (CTTC) stands as a bridge between past and present Peruvian cultural identity. Established in 1996 by a group of Chinchero weavers, it's led by award-winning author and Quechua master weaver Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez.

Alvarez learned her craft growing up in Chinchero, a small village located 30km northeast of Cusco. As a little girl, she says she spent her days looking after her parent’s sheep flock in the majestic Chinchero Highlands. She learned to spin and weave from an elderly woman whose skills sparked her interest in fine handmade fabrics.

Intertwined throughout her life, she says, have been the threads of her academic education and her indigenous traditions. Weaving provided Alvarez a reliable source of income during her college years at Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco. After she graduated in 1986 (the first in her community to do so), she received a six month grant to study textile history in Berkeley, California. Returning home to evaluate her career options, Alvarez says she decided on a path which would combine her academic and traditional arts experiences — working with traditional Peruvian Textiles and traveling to North America to teach her art.

The Birth of CTTC

The idea of creating a group which would preserve Cusco's textile heritage had its origins during the mid-1970s. Some weavers in Chinchero (including Alvarez’s own relatives) were deeply concerned that young people were turning away from weaving and that complex designs were being forgotten. Determined to revive their traditional textiles, this small group began to work together, using handspun yarn and natural fibers like alpaca, llama, and sheep's wool as a first step toward restoring high-quality indigenous textiles.

This informal cultural project ultimately developed into CTTC: In 1996, Alvarez and supporters from the USA joined these efforts and formed a non-profit organization with headquarters in Cusco. Envisioned as an educational and research center, the CTTC’s primary mission is to preserve and to promote high-quality traditional Cusqueñan textiles. The group also provides direct support to the weavers through the sale of their products.

CTTC is proactively preserving hand-spinning and reviving intricate weaving techniques through its research, demonstrations, and workshops. Long-forgotten designs are being woven again and ancient textiles (like the Aksu Inca dress) can be reproduced with similar colors. Following years of research and lengthy testing, natural dyeing techniques were re-introduced in 1999 to replace the synthetic dyes widely used in the Andes for decades. Natural fibers react differently to natural dyes and all CTTC’s weavers were trained to dye their yarn using dyes from flowers, leaves, vines, lichen, fungus, and cochineal.

"All of the un-dyed textiles they weave are in alpaca fiber as alpaca comes in many different natural tones,” explains Sarah Lyon of CTTC’s Education Department. “Sheep wool dyes much better than alpaca fiber. When you dye sheep wool, it comes out bright. When you dye alpaca, it comes out lighter — more like pastel colors." Weavers often prefer sheep yarn for the warp because they weave warp-faced textiles and use alpaca for the weft. The end result is a brightly-hued textile that is slightly softer due to the alpaca weft.

Peruvian Textiles — Techniques & Designs

All textiles are woven on a backstrap loom or on a four-post loom, a horizontal loom fixed to the ground with four stakes. CTTC is selling the perennial mantas or llicllas (women’s carrying shawls), ponchos, chullos (knitted hat), and chuspas (traditional bag) — but has adjusted to recent market trends by transposing traditional Peruvian textiles into modern and functional items like pillow covers, placemats, handbags, table runners or backpacks.

Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez says that globalization has affected many traditional practices within the communities. "Today plastic bags are everywhere, replacing our traditional carrying cloths — but the Pitumarca community is still weaving traditional striped potato sacks using undyed llama wool.”

She also says that the demands of the foreign markets drive additional changes. “We encourage the weavers to take advantage of the rich palettes of the natural dyes and, sometimes, we have our say in the color combinations or the size and styles of the textiles. But we never change the traditional patterns. This is something we have to respect totally. Some new items may not be typically traditional, but our members must weave at least two traditional pieces each year for their own use or for our store.”

Warp-faced weaving is the most commonly used technique in the Andes. Complementary warp (pallay) and supplementary warp (ley pallay) are two variations of this technique in which the warp creates the design and completely covers the weft. Wide textiles such as ponchos, blankets or bed throws are made with at least two handwoven pieces sewn together with ch’ukay, a traditional embroidery sewing stitch with a characteristic design.

“Ch’ukay are both functional and decorative,” says Lyon. "While they are physically necessary to hold together the two sides of the poncho or blanket, they are also decorative, and each community has developed its own pattern. For example, in Chinchero the weavers sew a zig-zag seam called q’inqu while, in Mahuaypampa, weavers use a seam that represents petticoats. In Chahuaytire, weavers sew chaska (stars or roses),” she says .

Designs and skills have been handed down from generation to generation. However without any written records for thousands of years, this customary transmission of skills nearly disappeared during the 20thcentury. CTTC is deeply committed to researching the extensive iconography of Peruvian textiles and has recovered over 110 ancient designs from antique textiles. Most designs reflect the weaver’s natural environment, depicting animal and plants or special events and all are woven from memory.

Visiting Cusco's Weavers

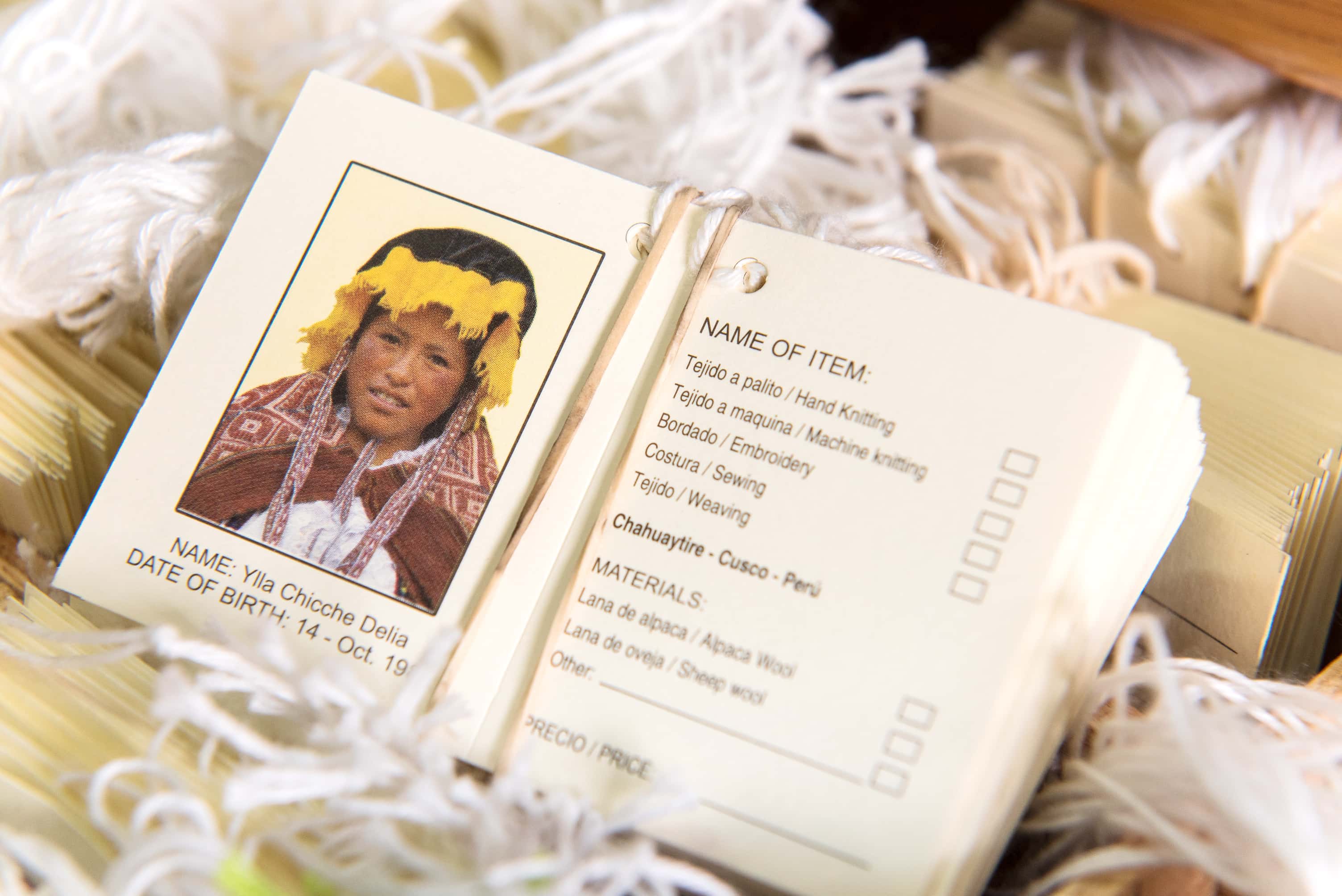

Each village has its own patterns, unique weaving techniques, and styles of clothing which indicate indigenous identity and the wearer’s community. CTTC has built a weaving center in several communities where the weavers meet once a week, working side by side and wearing traditional clothing distinctive to their village.

Chahuaytire

The village of Chahuaytire is located above the town of Pisac, 25 miles north of Cusco. Thirty-two weavers gather on Wednesdays in their large weaving center. They unroll their backstrap loom, tie it to a pole, and fasten the waist strap to the loom bar. Many men have learned to weave since the village partnered with CTTC and are known to work exceptionally fast.

Chahuaytire textiles are renowned for their stunning color combinations derived from naturally dyed yarn. The community produces double-faced textiles (complementary warp) in which the pattern is the same on both side but the colors opposite and some single-sided textiles (supplementary warp).

Chinchero

As the founders of CTTC, Chinchero weavers set an early example for other communities and remain the most famous weaving community of the Cusco area. The members offer free weaving, knitting, and natural dyeing demonstrations to visitors every day of the week. The characteristic features of Chinchero lliclla (blanket) is a plain-weave middle section in indigo blue or red cochineal with geometric designs on both sides.

Chinchero weavers have also created a tubular border patterned with eyes, called ñawi awapa. “Many other communities weave tubular borders similar to ñawi awapa," says Ms Lyon. "In Chahuaytire and Accha Alta, they weave the tubular border called chichilla which also produces an eye design while, in Patabamba, they weave a very simple tubular border called chinka chinka.”

Pitumarca

The small town of Pitumarca is a two-hour drive south of Cusco. Its weaving association is the only group to continue ticlla, a discontinuous warp and weft technique used by pre-Inca cultures such as the Paracas and Nazca. Elders within the community who had retained this technique are helping CTTC to revive it by training young members.

About 50 weavers of all generations gather on Saturdays in their weaving center. There, they practice their unique weaving skills — such as weft-faced tapestry weaves or the supplementary warp technique. Women and men learn to spin consistent yarn from a raw fleece at an early age using a pushka (drop spindle) and often spin throughout their entire lives. Weaving requires a good eyesight and beating the weft in place on a backstrap loom is physically taxing; older women and men who can no longer weave continue to spin, ply, and then sell or trade their yarn.

Santa Cruz de Sallac

Nestled at the end of a dirt road (and a slow 40-minute drive from the main road), the remote Santa Cruz de Sallac weaving center has a magnificent view of the valley below. About 45 adult weavers and 20 children are members of the weaving association supported by the CTTC since 2005. They meet on Saturdays, spinning, weaving, or knitting hats (called chullos) together.

The Santa Cruz de Sallac weaving community is known for practicing two unique Peruvian textile techniques: Watay can be traced back to the pre-Inca Nazca and Huari cultures; the weavers have revived this resist-dyeing technique with which they create the pattern of the Inca cross (called Chakana), a strong spiritual symbol of Peru. But perhaps their most characteristic skill is the hybrid weaving-embroidery technique. A plain-weave cloth is woven on a backstrap loom, then taken off the loom by the weaver who embroiders patterns onto it, using a needle and different color threads. The finished products look as though they were produced by a supplementary weft weaving technique.

Present Impact (And Future Plans)

Household incomes in the Andes are typically generated from a combination of weaving and livestock farming (and often mixing cash with the barter of goods). Through its purchase of artisan products, CTTC supports close to 600 people in the Cusco area. The group has established strong partnerships with ten Quechua-speaking weaving communities in the Cusco region and is currently working with 450 adult weavers in addition to elderly spinners and groups of children.

The CTTC museum also supports the community through its “Weaving Lives” exhibition, offering an educational journey through Andean past and present cultural identity. The exhibition describes the weaving processes and the origins of natural dyes, as well as showcasing the designs, styles, and the importance of woven textiles in both daily life and ceremonies.

Collecting high-quality vintage Peruvian textiles is another important mission and, through donations and purchases, CTTC has built a unique collection of ethnic Cusqueñan textiles. It currently includes nearly 1,500 pieces, with some rare items dating back to the 1920s and 1930s. CTTC also frequently shows pieces from this collection in temporary exhibits at other museums — but intends to open its own museum to exhibit their permanent collection once space and funds allow.

CTTC founder and director Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez says she has pledged herself to restoring community pride in these indigenous arts through the center's exhibitions and community education efforts. This may be a challenge for her: Cultural identities that were, in centuries past, quite literally woven into clothing have become looked down upon by young and urban people today,

Alvarez says, however, she believes minds are slowly changing: “Today, children wear their traditional clothing comfortably during festivals or celebrations. We have been educating in many ways, but we still have a lot to do — especially with city people.”