Bangladesh has a rich history of craftsmanship from airy Dhaka muslins, to breathtakingly detailed jamdani fabrics, and rich indigo blues, and it is home to generations of skilled artisans.

THE KINDCRAFT’s co-founder, Lauren Lancy, visited the South Asian country in 2017 on a handicraft development trip and met with several weavers, natural dyers, block printers, and embroiderers who are using fair trade practices.

Natural Dyes – Past and Present

Natural dyeing techniques in Bangladesh are often imbued with personal, cultural, and religious meanings. Throughout history, dyes were often seen as a reflection of a weaver’s mood and emotions – or were consciously woven into fabrics used for special occasions. With the advent of synthetic dyes in the 19th century, though, nearly all commercial use of natural dyes was eliminated.

In the 1980s, natural dyeing experienced a kind of renaissance. Local groups began to research and document what had been a rapidly fading knowledge of natural dyes and experts like Ruby Ghuznavi started to work on simplifying the dyeing process and to develop an economical and sustainable selection of dyes which could be competitive in the mainstream market.

In 1990, Ghuznavi formed Aranya – a fair trade brand which applies that know-how and combines traditional techniques with contemporary print designs. Its aim is to keep manual craftsmanship alive through the production of naturally-dyed, block-printed textiles. Aranya has grown steadily over the years and today, along with natural indigo brand Living Blue, represents a new beginning for natural dyes in Bangladesh.

Block Printing

To showcase these natural dyes, the team at Aranya uses a 350-year-old technique of creating floral and geometric prints using hand-carved wood blocks. Once Aranya’s design team has created a print, they pass that motif to a block carver who chips away at the wood until the decorative design is replicated. Printers carefully stamp these designs onto fabric and, block by block, create complex decorative motifs on sarees, shalwar kameez (a traditional tunic and pant set), men’s collared shirts, childrenswear, and home textiles.

Wax printing is a variation of block printing where printers use hot wax on the block instead of ink. The wax resists dye and the print is made from the undyed base color of the cloth. Printers choose this technique when they want to create a light print with a colored or dark background.

Aranya’s artists also employ another fascinating painting method, brushing ink onto the border of a saree fabric which is then also layered with printed motifs.

Textiles – Jamdani and Benaroshi Sarees

Within Bangladesh’s long tradition of handloom woven fabrics, the unique technique of jamdani weaving is especially well-recognized. Originating around 2,000 years ago from the delicate and breathable muslin weaves of Dhaka, jamdani became known as the ‘flowered muslin’ because its name, stemming from Persian words ‘jama’ (cloth) and ‘dana’ (woven motif), also echoes the words 'jam’ (flower) and ‘dani’ (vase or container).

Compared to standard muslin fabric, jamdani is muslin which is interrupted to embroider traditional motifs, weft by weft, within the weaving process. Colored, silver, or gold threads are inserted with bamboo shuttles between upper and lower warp before being stabilized by the plain weave.

Traditional motifs taught by master weavers to their students are woven by heart, often without the use of patterns. Each generation of weavers creates their own designs in response to their lives and emotions. Villages like this one in Demra-Narayanganj (above), just south of Dhaka city, are known for jamdani production. These village makers have developed a design process using jacquard looms to facilitate the manual embroidery work by repetitively lifting the warp threads of the motif’s section.

Despite their relatively high price and need of intensive labor–it can take up to four months to weave a single jamdani saree–these textiles have continued to grow in popularity over recent years.

Benaroshi sarees (below) are jacquard textiles made with metallic wefts that form its characteristic gold or silver motifs. They are a popular choice among Bangladeshi and Indian brides who wear red on their wedding day. Wedding guests and party-goers often opt for other bright colors like blue or green. Benaroshi sarees are valuable — a piece of clothing that a woman can keep for her entire life.

A Trip to Sirajganj

Located several hours northwest of Dhaka is Sirajganj (sometime spelled ‘Sirajgong'), a region known for weaving gamcha checked towels and lungi – a colorful, checked waist-wrap commonly worn by Bangladeshi men.

Sirajganj is also home to saree weaving factories. Though the number of weavers working in Sirajganj has been in decline over recent years, the ones who remain are often running at full speed in tin-roof workshops, noisy from the clackity-clack of wooden floor looms.

Embroidery

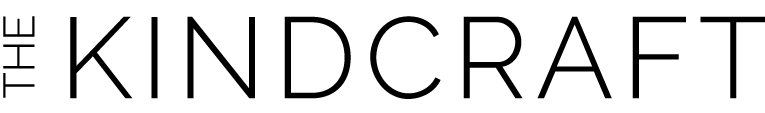

In Bangladesh, the art of embroidery finds many forms: Clothing, blankets, and arrases are adorned with colorful floral or geometric patterns — and sometimes used in a sort of figurative story-telling. Fair trade embroidery clusters (like this one in Uttara, a northern suburb of Dhaka) use techniques like mirror work, bubble stitching, dal chain stitching, and bhorat fill-up stitching as part of their masterful embroidery process.

When the embroiderers begin, they first transfer the design to the fabric. They punch small holes in a paper with the design drawn on it, carefully tracing the lines of its pattern. The paper is then placed atop the fabric and rubbed with a chalk solution, creating dots on the cloth below that will guide the elaborate stitching.

Nakshi Kantha

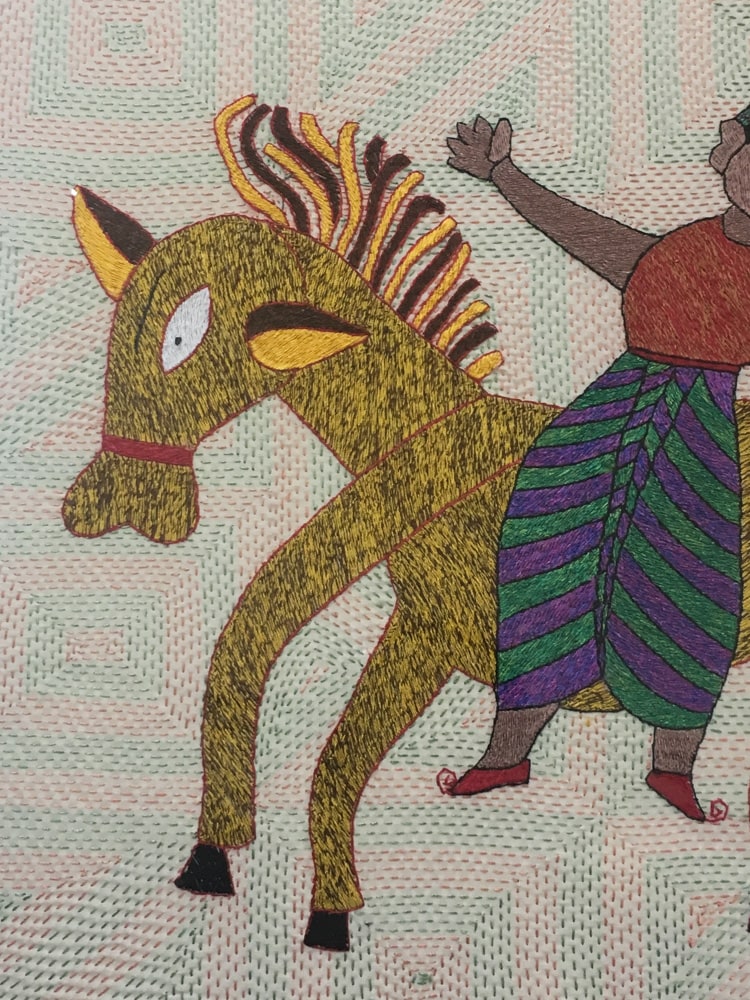

Handmade running stitch quilts, or kantha quilts, are a staple of every home throughout the Indian subcontinent. They are traditionally made from several layers of old sarees, lungis, or dhotis stitched together to make a single quilt.

Kantha quilts with colorful, patterned designs are called Nakshi Kantha, related to the word “naksha” which refers to artistic patterns. Common themes for nakshi kantha motifs include birds, lotus flowers, the tree of life, chakra wheels, animals, or entire scenes that tell the folk stories of Bengal.

There are few places in the world remaining where handmade textiles are still an important part of daily life. You'll find evidence of Bangladesh's traditional arts everywhere — from the crowded city streets of Dhaka to the peaceful villages in the countryside – and it's heartening to know that the country's most popular lifestyle retailer is an artisan-based fair trade brand.

As a designer, I came away from my visit feeling inspired by the possibilities of what can be made in Bangladesh — and impressed by the incredible skills of its makers.