Charllotte Kwon has come a long way since founding Maiwa as a one-woman business—both literally and figuratively. An intrepid traveller who seems as at-home in India as she does in her native Canada, Charllotte has grown her artisan textile company into a slow clothing brand, a supply shop for dyes and materials, and has also spun off a charitable foundation dedicated to assisting artisans. She also writes books, organizes tours, and leads the Maiwa School for textile and natural dye enthusiasts.

THE KINDCRAFT's Fiona Coleman sat down with Charllotte and her daughter, Sophena, recently in Vancouver to learn how they built a family business which supports makers around the world.

Origins of Maiwa

THE KINDCRAFT

How did Maiwa start?

Sophena Kwon

Maiwa started in 1986. The actual name "Maiwa" is from my Chinese side, which is my dad. He and my mum found this word that they both fell in love with. It just had this beautiful sound, something that the company could grow into without being like pigeonholed into something like "Charllotte Kwon Designs".

Charllotte Kwon

"Mai" is "beautiful" and "Wa" is "language"; "Maiwa" is "beautiful language" and it's the language that art speaks. We just loved it.

Sophena Kwon

In my mum's early 20s, she worked as a printer running a Heidelberg press but eventually got blood poisoning—septicemia—and had to have multiple blood transfusions because of the chemicals, heavy metals, and leads in the inks and solvents used in the printing shop.

While she recovered, she realized she couldn't go back to her printing career and so she began to try to find a more user-friendly, environmentally friendly way of achieving color. This led her straight into natural dyes, transferring what she was doing on paper onto cloth. She started silk painting and, because there wasn't a lot of literature on natural dyes available, she would travel just to sit with dyers and learn their recipes. She slowly started to build that knowledge and began teaching it and Maiwa started as her own work. And then, as she traveled, she started being so inspired by what she saw and the quality of the artisan craft. She would buy things just because she loved it. And slowly that started coming into the shop.

Charllotte Kwon

I was learning from people as I could afford to travel. I would try to find out so much about natural dyes, hand-weaves, and hand-spuns from people who had been doing it for generations, if not centuries, and yet they were not able to sell it. It just stunned me that this work was so well developed, so exquisite, so deep from centuries of refining. They weren't able to find a local market that would economically sustain them creating work of excellence. The local market wanted inexpensive textiles.

THE KINDCRAFT

There was no market for it?

Charllotte Kwon

No market. India is only now just having a local market that supports it. I mean—there's always been "tourist craft", but that didn't interest me. What I was really interested in was the work of excellence. The majority of craft belongs within its own culture, I think, for true craft. But some of it needs to be traded because there's that commercial aspect to craft. It's not art in the same way as fine art—it's its own entity.

Starting An Artisan Business

THE KINDCRAFT

How did the business start? And how many employees have you built up to now?

Charllotte Kwon

Now we have 40 staff here in Vancouver. It started with one... and then two... and then when I opened the shop on Granville Island, three.

THE KINDCRAFT

Tell me about Granville Island and the community of artisans there.

Charllotte Kwon

It's a very interesting story actually: It was an industrial area—and you know, this may be an oxymoron, but there were some very visionary politicians at that time in this city. In every city, artisans go into the kind-of crappy areas and they make them really funky. Then restaurants and bars come in and then the stores. That area becomes gentrified a little. And then the artisans are out and they find a new place.

And so the politicians wanted to do this social experiment of housing where you brought together wealthy people, low income families, and people with disabilities and gave them all a place on the waterfront. They kept everyone all together and their vision for it was that there would be anchor places—the food court and the big major restaurant tenants and so forth—whose rents would go towards making studios and stores available to artisans at a very subsidized rent.

Say somebody is paying CA$80 per square foot; An artist would pay $8 per square foot. We all pay percentage rent, so all our sales are transparent. The idea is you pay more rent as you came up as an artist, which allows more and more money to subsidize new artists. Here, we have monthly meetings to re-explain it to all the incoming people. But I'm now one of the paying people because I've gone through the whole ranks of 25 or 30 years down here. I'm now at the higher square foot price and completely support what I think is now $9 per square foot for an artisan to come in.

THE KINDCRAFT

Did you always have the shop and the workshop here?

Charllotte Kwon

No. It was originally out of my home and then I applied to Granville Island. There were 400 applicants and, the first place that I wanted, I didn't get. I already had one kid and I was pregnant with Sophena when they approached me for this new concept where artisans produced their own work and sold it in one space.

INDIA

THE KINDCRAFT

So you ended up, as you said, in India...

Charllotte Kwon

I knew that, wherever I ended up, I would be there for a very long time and so I had to love it. And it's very hard work, working out in villages. At that time, I was on my own: The kids were at home, because my mom was helping me look after them with my husband. People often will say "Why didn't you try to do it here with the indigenous people here in Vancouver?" You know—I don't know... it was something about India. It got my heart and I knew it had to be something pretty strong. I was a hyperactive child and, when my mother finally came to India, she said "I know why you like India... because finally something wears you out." [LAUGHS]

Sophena Kwon

There is no place on this planet that matches the skill level and has maintained an incredible connection to the production of cloth as India. The amount of knowledge they've held onto is due to the fact that their traditional garment is an unstitched cloth, basically. You have longhis for men with a five to six meter piece of fabric and a saree, which is eight meters long of fabric. Different regions in India will wrap it differently, but everything in how they present themselves to the world—their identity, their feeling that day—is all in the fabric.

Charllotte Kwon

As Sophena says: In India, if you know the cloth, you know exactly the area it's come from within 50 kilometers. But in the West, cloth producers are suppliers, not artisans. And if they're artisans, the fashion designer doesn't want to share that with anybody—so they're still suppliers. You don't know where it's from, what village it's from.... you don't know who's done it. And that invisibility has turned artisans into laborers.

Sophena Kwon

We now have our own sewing studio in India: It's in a block-printing in a village outside of Jaipur, but we only sew about two-thirds of our garment line there and one-third in our own studio in Vancouver. There's 6 to 8 people sewing at any time. It's all done in-house: We do French seams, flat felled seams, covered seams on certain materials. Our finishing is exquisite, which I am very proud of. If you actually opened up each piece of clothing, you'd see how much thought goes into the garment construction.

THE KINDCRAFT

At certain points of the year, do you all go to India?

Charllotte Kwon

The staff go there, they live there, our flat's there, we work alongside them. The studio and the house is all-in-one. Last year, eight of us were over there for six weeks in November, December. Then we were back for two weeks, then returned—five of us—for January, February, March. So we're actually gone quite a bit. On each trip we log between 4000km-6000km on the road, going out to visit all the villages we work with—from Kutch to Bengal and from Himachal to Tamil.

When we're here, we're full-on... and then we're gone. And when we're all over there, it's a totally different life. You just can work on ideas over there. It's so creative. We have weavers and pattern-drafters and dyers and block-printers...

Sophena Kwon

I can go from an idea and a sketch in the morning to a pattern and a prototype and then a final fitting in one day. It's amazing.

Charllotte Kwon

When we went in, we bought all the raw materials. We still have a complex accounting system, like those old type of banking books... we would buy the organic cotton and the dyes and which goes in as a debit to their book as they do the weaving or the block-printing. But we've found that the hardest thing was to convince them that they should buy such high quality raw materials and so we ended up having to control that process.

THE KINDCRAFT

The whole process from start to finish?

Charllotte Kwon

Controlling the process and the quality, but not the design. We're not designers. Once we call ourselves designers within their world, then we lose something very important. We're designers of the clothing because we have to fit a western world. We're designers of the size of a tablecloth, for instance.

Sophena Kwon

We want the cloth to speak of the people who actually made it, so we don't interfere with that design element because you want to look at a cloth and know that the weave structure comes from Andhra Pradesh or that a block-print comes from Kutch [District, India]. And that identity should actually be really evident in the cloth—but then we will make products out of that beautiful fabric or craft that are very relevant and useful in this part of the world.

THE KINDCRAFT

So you're separating the clothing and the cloth?

Charllotte Kwon

Often, it's the cloth that doesn't get recognized by the fashion industry and it's cloth that makes everything. A shirt is a shirt, a dress is a dress — I mean, it doesn't really take that much to draft a pattern. But the cloth is what all designers are looking for.

THE KINDCRAFT

You don't interfere at all with the artisan's work?

Charllotte Kwon

We will push. Some artisans will ask 'Why is my work not selling?' and I say 'Well—you know we've talked about color...' because you do need to know who your market is. This gives us opportunities for helping them with marketing. We work very transparently with costing. We're very hard on quality control.

Sophena Kwon

That's probably our main thing: It's so awkward for quality control to come from within a community because, of course, you don't want to be the person next door saying 'Your work is falling behind or below the mark.' It's way better if that comes from the outside of the community—like from us.

We can say 'This is "Maiwa Quality"... and this is "Not Maiwa Quality".' They can sell "Not Maiwa Quality" to whomever they want but, to get that price point that we're willing to pay, it has to be at this level. We're just encouraging them all the time because that pushes their skill level up.

Charllotte Kwon

We have a lot of meetings. We work mostly in villages and there's a lot of the stuff that can go south in a village. You just get it on the table and you start... and you know, there's screaming that goes on. It's not a peaceful place. People will yell at each other and so we just keep bringing them back to the table and talking through it.

Of course when we ask them 'What does everybody want?', the first answer is 'more money'. We then say 'Okay—Let's unpack all that and see how we could do that.' And, in the end, they come up with almost all their own solutions. About quality control—we do it out front, but we take the stand to say 'No, that's not going to meet it.' Occasionally there'll be somebody who will step up and say 'I think if I was paid, I think I could do quality control.'

THE KINDCRAFT

So you actually have quality control within the village?

Charllotte Kwon

We rarely have it within the village, but we'll have it outside where they have to bring it to some place. We have a home in a village outside of Jaipur and so people can bring things there. We pay incrementally, so we pay on the order, pay on the raw materials, pay at certain times. But to get their final payment, there has to be quality control.

Design

THE KINDCRAFT

Is there a "Maiwa Look" that ties all these different artisan products together?

Charllotte Kwon

I guess we don't want to look "ethnic", even though that we could easily look that way. We want to look classic.

Sophena Kwon

Timeless pieces. While we've had other designers with us in the past, right now it's mostly me and my mum. I just feel so lucky that I'm working with the nicest fabric ever—like, I went through fashion design school and had to buy cloth at some awful places. And now to have this quality of material is a dream. And also to work in the natural dye palette, you don't have to fashion trend or color trend. All the colors do go well together. We are also aren't trying to make "spring collection" and "summer collection"; we're continuously designing so that, when we put our collections together, they're cohesive.

THE KINDCRAFT

You don't actually design seasons?

Sophena Kwon

It doesn't really work because sometimes we'll have, like, a thousand meters of hand-woven fabric but it will be two years out and then it'll be delayed for six months. That's just human... and we can't stress ourselves out. In Bengal, there's this great story of how it took 30 days to work this amazing loom which was 30 meters of fabric. But almost at the end of warping, a cat jumped on the loom and made a complete mess of it and that delayed it 30 days again. So as designers and as people selling our own work, we've really done quite a good job of taking out the stress of when things are delayed—because it happens all the time.

Charllotte Kwon

We are highly inventoried. We are not using a "just-in-time" accounting inventory system [LAUGHS]. I only feel good when I have lots of inventory to help us through some of the times Sophena's been talking about because it does happen. Things do go south. You also get excuses, too—to which you then go 'Hmmm...I'm not sure that's exactly what was going on, but—'

Sophena Kwon

'Not the "cat-on-the-loom story" again!' [EVERYONE LAUGHS]

With our garments, a lot of it's hand-woven, so I like to do flowing garments and a lot of oversized pieces that very flattering or many different shapes and sizes. We don't do anything super-structured or over-tailored; nothing fussy or over-designed. All of our pieces are meant to layer and be worn in lots of different styles.

Another thing that we've done since day one—which I love—is that we've always offered a free alteration and free mending with every single garment, for the life of the garment. We've had things come back after 15 years of being loved and someone may be like 'I'm not really into a long skirt anymore. Can we crop it? Make it like a mid-calf or ankle-length?'. Okay. So let's do that... let's keep that garment going.

Charllotte Kwon

And we can sell you dyes so you can over dye it!

THE KINDCRAFT

You obviously know your customers really well. Is it a pretty diverse group?

Sophena Kwon

We have a huge local support and now I think people in their 20s and 30s are finding out about us more and more and so it's getting a nice kind of energy around it.

Charllotte Kwon

Daughters who would come and shop with their moms have a nice feeling about Maiwa, so they come back and they're finding things—which is inspiring.

Educating and Connecting

THE KINDCRAFT

Did starting Maiwa Supply and a school of textiles go hand-in-hand for you?

Charllotte Kwon

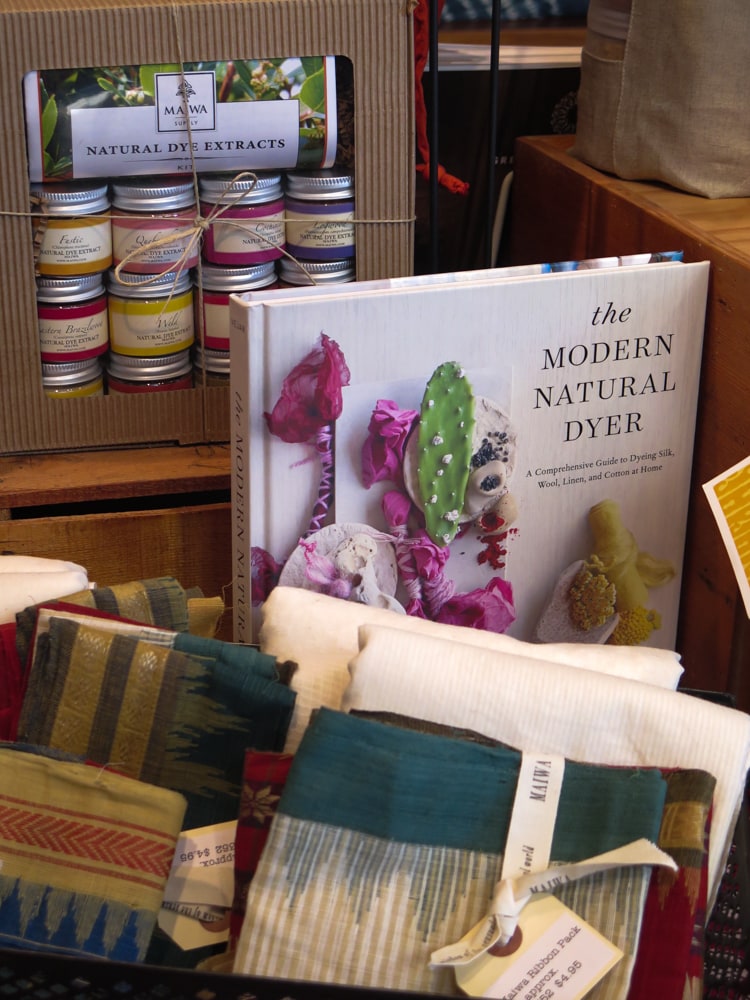

You probably can't imagine it today, but there was a time when our landlords couldn't rent the spaces on Granville Island. So they gave me a second space and I had it for six months, rent-free. And what happened was that people would see me working and they'd want to know 'Where do you get your dyes? Where are all these brushes from?'. So I started Maiwa Supply.

The supplies came first because people want to know what we were working with. When people came into the shop, we were doing little workshops and demonstrations around a huge table so people could try their hand at things. But then people didn't just want 'make-it and take-it' things. They'd say 'We want to learn how to draft a pattern like you guys. We want to learn how to dye like you guys.'

Now days, "natural", "slow clothes", and "slow foods" are more in people's vocabulary but, at that time, natural dyes made people say 'What is that?' We needed to educate people about the products and organic fibers. Seriously, people didn't understand it or hadn't heard about it. Now it's not so much that people don't know about it, but we don't have young people who know how to sew, know how to weave, know how to dress a loom.

We felt like we needed to educate in order to keep makers—and making—alive. So we started a school which brought in international teachers.

Sophena Kwon

It was so well received that first year that we kept doing it as a two month kind of thing in the fall. And then we started realizing that we're getting such incredibly amazing artists in and people were signing up for their workshops as — so we created some foundation-level, skill-focused workshops in the spring: "Intro to Dyes', "Intro to Weaving", and so on to give people a skill set so that they could really make the best of when the international artists came in. And then, when we started doing all year round, we were like 'Okay—we're doing 75 workshops a year. Let's call ourselves a school.'

Charllotte Kwon

It's grown from strength to strength, because I really love the combination of makers and finished works. We try to create a connection all the time between the maker in India and the wearer—so they can come together to learn about each other and to learn about culture. Somehow the world is a bit disconnected, but there's people around the world whom you can connect with that way.

THE KINDCRAFT

Have you noticed a resurgence in support for that idea in the last few years?

Charllotte Kwon

I would say there was a big support in the 80's. And then the 90s came... and they sucked. I thought 'Gee—I guess this is all just a trend.' But we've never not done the same thing. People would say 'You're still in India? Isn't India, like, yesterday? Why aren't you in Guatemala?' and I was like 'Because Indians are still there! There are still those craftspeople there and I can't leave them.' I feel very hopeful that it's all sticking now: I think this generation, whether it's about food or beer or cloth, are curious about makers. They're a bit uncurious about the world and travel. They're scared, I think. They're timid.

Sophena Kwon

She's not talking about me... [LAUGHS]

Charllotte Kwon

[LAUGHS] No! But I think that "making" will lead them out to realize that the world is their home—not Vancouver, not London, but the whole world. Maybe not as much in the UK, but here in North America we've got a huge neighbor who makes our young people a little bit scared of the world. It's like everything in the news... makes people un-curious.

Making—and the connecting that making does—whether you're brewing artisan beer or dying some yarns for embroidery, you have to be curious. 'You've got to find out how was this made historically? Where did this color come from?'

Colors and Dyes

THE KINDCRAFT

What does color mean to you?

Charllotte Kwon

[Makers in wealthy countries] have so much access to color, we can get anything we want. But in a village in the desert in India, makers get whatever they get—so color becomes something that they have no control over. They're told 'these are vegetables dyes' when they're actually toxic napthol dyes that they have no protection from or knowledge of. All the drums are never in Hindi, they're always in English—except for the skull and crossbones. And they've lost the fact that they can grow henna, they can grow indigo, they can grow all these things.

Sophena Kwon

Mum and I are both natural dyers. That's our medium of choice but, as you probably saw in the supply store, we also sell synthetic dyes. We sell Procion MX and Ciba acid dye and good quality, European made fiber-reactive exhaustive dyes that are high quality and aren't necessarily as harmful on the environment. So there's science on making very good—or low impact—synthetic dyes... but those are never the dyes that you see when you're in the developing world. We're still making really awful petroleum-based synthetic dyes that are illegal to sell and use in North America and in Europe, but which are still dumped in Africa, in India, in Vietnam.

Charllotte Kwon

And those dyes are developed for countries that have water, so they're highly saline. And in India, it destroys the water table. But in Europe, it's different: They don't permit cloth to come in if it's got azo-based dyes. That's not banned in the U.S. or Canada, so companies can still order all that stuff and they can still dye it. And, yes, I agree synthetic have cleaned up their act a lot, but the synthetic dyes that are being used in these countries... [LONG PAUSE] They need to have industry, but we need to have better educated buyers. Nobody wants to use their power to do bad. Really, they don't. But the vast marketing ability of the fashion industry makes everybody just go 'It's okay...'. It cannot be okay. It's not possible.

THE KINDCRAFT

I had a conversation with [natural dye expert] Ruby Ghuznavi about the commerciality of natural dyes: Getting consistency, how to do larger batches.

Sophena Kwon

And natural dyes usually exist on a human scale. It can't exist in a large mass production scale...

Charllotte Kwon

But that's what makes it beautiful to own!

THE KINDCRAFT

It sort of leads onto this education to embrace the variations in natural dyes. Beauty in the "imperfection".

Charllotte Kwon

The biggest question at the till is 'Is it going to fade?' It's going to fade—but more beautifully than you ever can imagine. That fabric gets better because it started out as natural and it'll be the one garment in the closet that you don't throw out. Things fade and get old. It's beautiful. It's those things that you cherish.

Sophena Kwon

I've worked a lot on the floor of the shop and it's just so nice to be educators. Often, I say not that something will fade—but that it will change. As a natural dye, you have so much more complexity in how the color actually has evolved to be what you're seeing. There's a mordant. There's a complexity in the plant. So you're seeing a lot of different molecules happening to create that color whereas a synthetic dye is made in a lab and it's very one dimensional. When it fades, it goes dull. But natural dyes can become more lively. A natural-dyed garment will actually change and some dyes become more complex. Some dyes will become darker with age and some dyes will definitely become a little bit lighter but still have a very complex make-up because of the plant that's behind it.

THE KINDCRAFT

Everybody thinks you just have to accept wide color variations when natural dyeing, but I was really interested in reading about your rigorous testing process.

Charllotte Kwon

We have a whole test kitchen that goes on all the time, test dyeing, and then we can tell the farmers really early 'I think we have a problem' or 'Man—you got the best thing! What's happened?'. We know as soon as it comes out of the field. We test it. We know. So then for us to standardize it, we will keep our very strongest and we'll blend it. It never ages and never disappears.

We're like vintners. In 2014, we got an amazing madder with so much alizarin in it that I had to change all the recipes. 'And then I thought I should keep this and I'll blend it!' because the texture isn't going to be quite the same. And so we still blend that and we blend our cochineals and our indigos.

THE KINDCRAFT

Is it almost a re-education for some weavers to work with natural fibers and dyes?

Sophena Kwon

It's so much cheaper to be working with synthetic dyes and materials so, if there isn't a market or a buyer for it, the skilled artisans that we get to work with won't produce with natural fibers and natural dyes. So Maiwa has been substantial in the sense that, when we do partner up with an artisan, it's for the long term. A lot of our relationships with artisans are 15 to 20 years long now and often they'll say they never would've returned back to natural dyes if Maiwa didn't come along at this crucial time. And that whole body of knowledge might have been lost.

Charllotte Kwon

If everybody just owned one naturally-dyed piece... and it's just like our choices of organic food, you tend to buy it if you make organic food you tend to do more cooking at home because you can't afford so much. You're making more of an investment so you don't buy as much.

That whole idea that we have a right to cheaper clothes—We're not spending less on clothes. We're just buying more of the cheaper clothes. Closets are getting bigger. Everybody's got walk-in closets now.

THE KINDCRAFT

Everybody's just got too much.

Charllotte Kwon

Everybody's got too much! We're producing too much and the fashion industry is just not getting brought up to task. But, you know, the food industry really got taken to task about what we're putting in our bodies and it's really become a public issue. People now have to make their own decisions because there's enough education out there on organic foods. But we're not bringing the fashion industry up to task and they're still using their massive marketing power to make people feel okay.

The fact that Primark is producing $10 disposable dresses—it's insulting. It is. We've gone backwards. They're saying they're actually paying more and the reason they can do that is because it's their systems they're saving their money on. No, they're not. They're abusing... and so are all of us. We need to educate everybody to make better choices and, if you make the choice, than you have to apologize. You have to go 'I'm sorry. I know it was a $10 dress and I really shouldn't have done that... but it was cute.'. You know—fine. But don't think that it's okay to buy a $10 dress.

Textile Tours and Charities

THE KINDCRAFT

Why did you start your textile tours?

Charllotte Kwon

I was approached to do that first thing in 2008 and...

Sophena Kwon

Before she did that, she would always say 'Sophena—shoot me if I ever say that I'm going to do a textile tour!' [LAUGHS] Because she had never been on a textile tour...

Charllotte Kwon

But I was spending an awful lot of time helping people get to India. You know people would always come to me: 'How can I go to India with my husband? Can you give us an itinerary?' I would do people's private itinerary. And then one day somebody walked in from a tour company and said 'Somebody came in with one of your itineraries and it was fantastic. Would you be interested in doing a tour?' At first I was like 'No-no-no' but, one day, she came back and I was like 'Okay'... and so I developed the first tour.

On the way over, I was just about throwing up on the plane thinking 'What have I gotten myself into?'. I'm not very social, especially in the mornings. But then... I absolutely loved it. It works so "on-the-ground" in India and out in the village: You take a bus out there, a train out there... you work. When you come back, it's hard to explain what you've seen. But it's fantastic.

THE KINDCRAFT

All in India?

Charllotte Kwon

I've also done Morocco and Mexico because I've worked in those places, but India is the continuous one every single year. And I what I found was two things: I got inspired to see India through all these eyes and I got inspired by the artisans because we do a lot of educating before they go to India about artisans, about their situation, and why craft matters.

It's never lost on any of us that we take all their work away and sell it in a very far-away place. And as much as you try to include them in, you know, showing them ads and the online shop and everything, it's never quite the same as when 22 people get off the bus who really understand what block-printing is. They're ready to spend a day, be educated, take a workshop... and they go nuts over it. And the artisans are watching and I tell them 'Watch what they pick up and watch what they put down.' That's market research, right there. The people going on the tour—they're not cheap tourists. They feel they've got something so much deeper. They immediately get to benefit from our 30 year relationships and they're immediately welcomed like family. It's just fantastic. So now, I do love running them.

Sophena Kwon

I tell everyone that if you go on a Maiwa tour and it's your first time to India, it's like you've gone 10 times. It's on your 10th trip, having returned to places and having familiar people open their doors and homes to you, that's the experience you're going to get. There's no kickback, no commissions—we pay the artisans for demonstrations or workshops. A lot of tours take an artisan's time and then, you know, kind of encourage their group to buy things. And that just puts everybody in a tricky...

Charllotte Kwon

I don't like craft being in charity. It shouldn't be a charity response: 'I pity these poor people and therefore I better buy their stuff'.

THE KINDCRAFT

So then let me ask you about your Maiwa Foundation. How does it work?

Charllotte Kwon

The Foundation started in 1998. Originally, the idea was that artisans' issues are often quite immediate—their well has collapsed and they need to drill a new one, or they need a bicycle or whatever. Working there and seeing the need, we decided to offer CA$500 to $1,500 grants or CA$3,000 to $15,000 no-interest, long term loans. And so we've started the foundation with that in mind and got our certification, which took quite a few years.

From 2001 on, we have fundraised about CA$50,000 to $85,000 per year and, of that, Maiwa is still the biggest donor because we do auctions of the artisan's work. And now, after all these years, the artisans have seen the power of the Maiwa Foundation and they're sending things into auctions. They want to support it and they want to see the money be there.

Everything's transparent so, if somebody from one village takes a loan or grant, everybody that we work with knows. So, this is a neat organization—because it's theirs. We try to respond quickly—within two weeks of a request. They don't have to know how to write. They don't have to sign anything. We send somebody there with a recording instrument and we ask them 'What do you want? What do you need the money for? What will we see when we get there?'. We send people out to interview them and everything can be just socially talked about.

THE KINDCRAFT

Since starting the Foundation, how many artisans do you think you've helped?

Charllotte Kwon

Thousands. If you think about the {Kutch] earthquake and tsunami alone, with getting people back to work. We won't help them with housing because, if we do, it just means the government won't. But we'll help them with their studio, with their block printing table, with their wells, with getting things translated, with whatever they need.

Sophena Kwon

There was something quite recently with leather workers. We were actually trying to get them to come out to Vancouver and, in the process of getting their papers and their passports, discovered they weren't actually allowed to leave the country because they were under the grips of a gang money lender who was just basically abusing the fact that they needed to borrow back in the day....

Charllotte Kwon

Well they borrowed $1,000—which became $22,000 and they had no idea how it worked. They were indentured by that, so we helped them out with a long term, no-interest loan and then got a micro-lender to manage it. And now at any kind of craft council or conference they attend, they have to speak about debt. People don't talk about debt—here or there—but they need to talk about: How they got into it and how they got out of it.

Sophena Kwon

And they pay off some of that loan just through product sometimes, like a certain percentage of orders that we place will go back to paying back the loan.

Charllotte Kwon

Now they've learned that when they take a loan now, they have to cost that into their product.

The Present and Future

THE KINDCRAFT

What's Maiwa working on now?

Charllotte Kwon

We're doing a line of yarns: "Honest Yarns", it's called. That's all organic—naturally dyed, natural mordants and everything—so that's one of my little projects which is really exciting.

Sophena Kwon

And for me, my favorite... Well, I love everything I do in the company, but I think teaching has become big for both of us as well. We were just teaching a two week natural dye workshop out in Penland, which is like the "Hogwarts for Makers", basically, tucked away in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. It's an extraordinary school of craft. They have every medium there and one is not higher than the other: textiles and glass and wood and clay and jewelry and goldsmithing and ironsmithing... they're all happening. What is not taught is lost, so to keep teaching natural dyes is, I think, so important for both of us. We both teach separately, but to teach together is a dream—especially somewhere like Penland.

Charllotte Kwon

And then Sophena is doing these Indigo Socials which are so fantastic to get young people hooked...

Sophena Kwon

I call it a gateway experience [LAUGHS]. They're like pop up workshops. We collaborate with different spaces and like-minded businesses in Vancouver. One of my favorite places is where I'm going to be doing it in two weeks is in the courtyard of a wood shop. I've also done them in my boyfriend's fabrication workshop. I've done them in other stores. I've done them in spaces before they've been renovated to become other things, so almost like putting good energy into this space. And then 50-80 people come—they sell out in like a day, which is crazy.

I never dumb it down. It's not a simple workshop. It's got a ton of really valuable information and goes into the history of color, the botany of the plant, how it's harvested, how the dye is taken out of the plant, and how we get it and grind it. We cover the whole chemistry and alchemy of making the vats and all the different recipes. And everybody gets the two meters by one meter of organic cotton to work on, so you're paying CA$60 to get into the workshop and you're leaving with something that you've made worth more than that.

There's a huge demand and I thought that I would definitely exhaust it in Vancouver. But people keep wanting to come back again because, once they see things start to get revealed, they get so many ideas and say 'I want to bring this person next time!'. People keep coming and amplifying it out. So many people have been introduced to natural dyes through the Indigo Social and then sign up for a Maiwa workshop... and then maybe they're on this other path. So it's a really nice way to get people kind of into this kind of community and let them know what we do and how we work.

THE KINDCRAFT

Any exciting plans for the future that you can share?

Charllotte Kwon

Well I guess continuing to build the school but, probably a little one on our side, is that we want to move our studio in India. We've lived out of suitcases for 30 years so, you know, in a dorm basically. A very beautiful little dorm, we love it. We're pretty set up there but, right now, we're a bit spread out and a bit compromised with the fact that we're one of the last natural dyers in the area. So we're going to be building a facility really, really close on a farm for doing all our sewing and our dyeing. We do textiles all over India, but we'll bring them to one place that staff can feel at home, some of whom are getting married and having kids. And as we go back and forth, there needs to be a feeling of home.

So it's time now to do that and that's exciting because we want to build off the grid. We want to build solar and where are we cleaning our own water to neutralize some of the mordants and be able to reuse the water. So that is at a whole other level of experimenting and we've got an architect and a botanist who says we can clean all our water with plants. It's just a lot of interesting things from that side.

And, you know, keep it all together.

THE KINDCRAFT

Where do you find the time?

Charllotte Kwon

Well there's an amazing team. I feel very much like, I don't know, I just sit around and give my opinions. I would like to write more. I'd like to have more time to write and get the stories of the artisans in writing. I think it's incredibly important and so that's why these guys are taking on more and more and more...

Sophena Kwon

But also, mum works two years out. She is the one who is planting the seed that then we slowly, as a company, get to those destinations eventually. But she works two years out with planning symposiums, planning building projects in India, starting with a new group.... she's very much envisioning everything and then she has a really competent crew around her that help manifest those things and make it happen.

But, yeah, for sure: The captain of the ship right here. [LAUGHS].

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.