Japan's Tokushima Prefecture is steeped with aizome indigo tradition. This region of Shikoku island has a legacy surrounding the polygonum tinctorium indigo plant, which was first cultivated during the Kamakura Era.

Almost 300 years later in the Edo period, people planted indigo in July so that if October's typhoons ruined the rice harvest, they would still have indigo. Tokushima became Japan's largest indigo producer, and the region prospered for this reason and due to the great rise in handmade washi paper production.

Contributor Laura Wheatley recently traveled to Yamakawa, Tokushima to visit Awagami Factory and document the washi-making process and the careful dyeing of these handmade papers using local indigo dye.

The Fujimori family established Awagami Factory (Awa Paper Mill) in 1825 and has had significant influence on the washi paper-making scene since. This is particularly true in the Tokushima region, which was previously known as Awa. Despite economic hardships following both world wars, the Fujimori family persevered, keeping the Awa washi production alive. Seventh generation paper-maker Minoru Fujimori was honored with many awards by the Japanese government including the "Sixth Class Order of Merit, Sacred Treasure". Furthering his exploration into the art of washi, he created aizome washi. This indigo-dyed paper took the world by storm when it was first unveiled at the at the Paris World Fair in 1878.

Today, eighth generation paper-maker Yoichi Fujimori and his wife, master dyer Mieko Fujimori, run Awagami. Together, they sell to clients in over 30 countries: paper distributors, interior design companies, and the government of Tokushima who orders paper for official certificates. The family also works to promote the art of washi on a global scale by organizing workshops and hosting artisans.

When I meet Mrs. Mieko Fujimori, she tells me that she was taught by her mother-in-law who was named a Living National Treasure for her indigo dyeing skills. Her eyes light up when I ask her why she wanted to learn the craft: "I was compelled by the beautiful, sensitive nature of the indigo process," she said.

Taking in my surroundings within the workshop, I see sheets of washi drying on racks; some of the darkest blue hues, others faded in an ombre effect, known as bokashi. Showing me a small, wooden door on a wall, Mrs. Fujimori opens it just enough to climb in and retrieve an airtight container full of sukumo. Peering inside I see furled dried leaves of the indigo plant. Awagami purchases the (quite expensive) dried and fermented sukumo from indigo farmers in the Tokushima prefecture. It is known as "Awa-ai" which refers to the region's old name, Awa, and "ai" for aizome.

Mrs. Fujimori then guides me to an indigo vat in the ground that is covered with wooden planks. As she lifts them, I am greeted by the intense earthy, fermented aroma of indigo dye. The mix includes water, sukumo, caustic soda, and hydrosulfite which helps to improve the color quality while eliminating excess dye and unwanted particles. The ideal temperature for the fermenting dye is 20°C, which can be a delicate balance to achieve.

Pulling on indigo-stained gloves, Mrs. Fujimori proceeds to dip a long sheet of dampened white washi into the deep vat. She explains that the washi has been brushed with a mixture of konnyaku powder and water boiled into a sticky substance which makes the paper strong enough to withstand the dyeing process. As she raises the washi out of the vat, the color turns from brown to green as the dyed paper is exposed to oxygen. I follow Mrs. Fujimori as she walks into a sun-drenched room where the fresh air hits my face. She hangs paper on a pole between two wooden stands.

Gently washing off the excess dye with a water hose, Mrs. Fujimori smiles upon seeing my expression: I'm watching with amazement as the color turns from greenish brown into the most brilliant blue. It feels like magic!

"It's my favorite part of the process," she agrees as she rinses the paper and checks the color, deciding if it should go back into the indigo vat for a longer dip. Approving the color, she puts the paper in the tub to soak for an hour, stirring it gently to remove any roughness or excess sukumo. Then the smooth washi is hung on a drying rack and - once it's dry - the paper receives the stamp of approval from Mrs. Mieko Fujimori.

At the end of the process, she tells me that there are a few traditional washi mills left in the area, but only Awagami makes this special indigo-dyed washi. She is very proud of her technique, which she feels yields beautiful results. I heartily agree.

After learning about indigo-dyeing, I'm eager to see the Awa Paper Mill washi-making process. Mr. Yoichi Fujimori shows me the workshop, explaining that he introduced machine-made paper for modern-use, essentially merging their heritage methods and contemporary practices. Awagami continues to make traditional handmade paper, but now they also produce products for modern applications: inkjet paper, artisan wallpaper, bound journals, and contemporary-style artwork.

Traditional Awa washi is made from a mixture of mitsumata and kozo (mulberry), depending on the type of paper that is being made. Kozo is grown nearby on Mount Kotsu and harvested in the winter. After the harvest, kozo is steamed and stripped of its bark, dried, and stored.

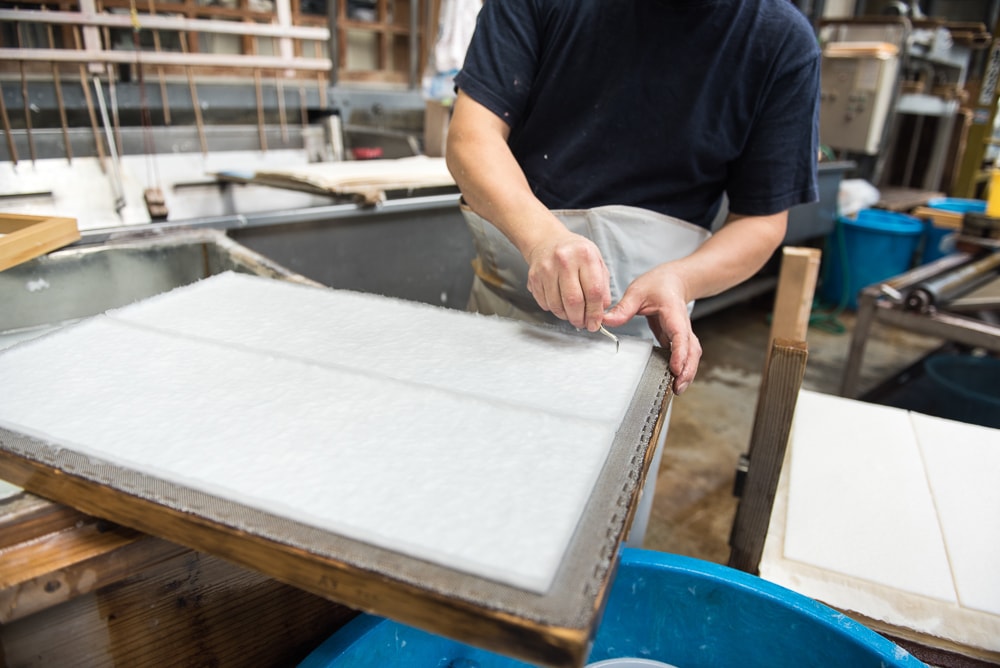

Later, the kozo is soaked and the dark-colored layers are rubbed off. It is then cooked in an alkaline solution to soften the fibers, break down starches, and remove impurities. The strips are then beaten until the fibers separate, and mixed with water. A thick gel-like plant substance known as "neri" is then added to the pulp. Awagami uses the Nagashizuki method of paper making, utilizing a wooden mould to constantly and consistently disperse water over the pulp so that it drains out of the screen at the correct rate. The strength of the paper is determined by the technique of the artisan.

Once the paper is removed from the screen, it is laid directly on top of the last paper. A weight is set on top so that the paper drains naturally, and then it is put into a press. In some cases, the water is vacuumed out. The paper is then set on a drying board in a temperature-controlled room. When the paper has dried fully, it is checked for quality and approved or rejected.

I am fascinated by the rich culture surrounding indigo-dyeing and washi-paper making. As I leave Tokushima to continue my journey through Japan, I remember what Mrs. Mieko Fujimori told me about the uniqueness of their heritage crafts and modern products. After experiencing these intricate processes, I now understand what she meant.