In the foothills of southern Mexico's Sierra Madre de Oaxaca mountain range, you'll find Teotitlan del Valle — a village which proudly retains many of its traditional Zapotec customs. Long famed for its weavers and natural dyers, Oaxaca craft workshops continue to produce high quality textiles for the world.

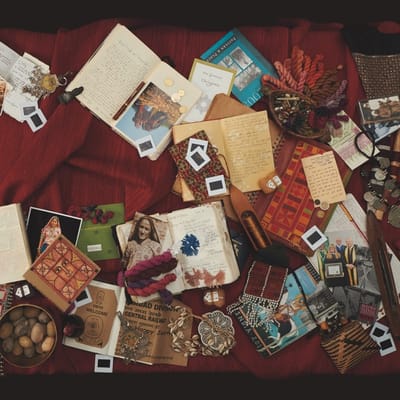

Contributor Emalese Russell visited one such studio, Porfirio Gutiérrez y Familia, and photographed their workshop for THE KINDCRAFT. We were so intrigued by the images she sent that we reached out to founder Porfirio Gutiérrez for an interview. Conducted over several sessions, he gives unique insight into the concerns of indigenous artists and how his family's tradition connects to a global movement towards naturally-made products.

THE KINDCRAFT

Could you tell me a little about your family and their history of weaving and dyeing?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I come from a really big family... 11 kids. We are a family of weavers specializing in natural dying. Not too long ago, I was looking at some pictures of my grandmother as she was doing the carding and spinning. Our family also harvested corn. As far as my dad can remember, this tradition goes back many generations in my family and, in Zapotec culture, it goes back two thousand years.

THE KINDCRAFT

You started weaving very young, right?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

When I was growing up, we were always involved and helping different aspects of creating each weaving. At 12 years old, I began to weave and my father taught me some of the basic knowledge but, like I said, it's just part of our DNA. We grow corn and we weave. I remember playing my under my father's big loom and watching a new design emerge, line by line and just trying to understand what's happening there as my dad uses his hands to give life to a design. I thought it was just incredible as a kid watching him, playing on his loom with his tools.

The other aspect was collecting the plants. On special days, my father would take us up in the mountains to collect the plants we needed for making our dyes — almost like a pilgrimage. As we'd hike up into the mountains, he'd tell us stories about the plants and the most perfect times to collect them. He would talk about the importance of understanding the power of nature, the cycles of the rain. What he was trying to tell me is, basically, we need to care for our Mother Earth. It's not only our home — we eat and we make art with the material that the Mother Earth provides.

THE KINDCRAFT

Is that attitude part of Zapotec culture or something specific to your father?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Older generations were absolutely aware of nature and the importance of caring for Mother Earth. I was just talking to my dad not too long ago because this year we didn't have a lot of rain, which affects lots of things — especially when you're working with natural dyes and still grow your own food. My dad said that, 10 or 15 years ago, there would be a mass asking for rain. Things are changing. You don't see that anymore.

When I was growing up and watching my dad, there would be this sadness in his face when we'd visit the cornfield whenever there was no rain, no water. It's one of the very few times I've ever seen my dad really get sad for things. Trying to understand what was going through his mind: The importance of the corn or having enough rain to for us to drink and to grow the plants where we get our colors from.

My dad would often say that, when he was a child, there was no one in the community who's say "This is my land" or "This is mine." There's an incredible part of Zapotec culture called guelaguetza [an indigenous sharing system of collaboration and exchange in Mexico] that came about to share things you might have when someone else is in need. If there's a wedding, they might need bread, tortillas, corn, beans. So I'd come and say "I could bring you a pig" and this is guelaguetza that you can use to feed your guests. And whenever I need it back, I'll just ask you for it and you'll give it to me. So it's a way of helping each other in a tight community.

NEW MARKETS FOR OAXACA CRAFT

THE KINDCRAFT

When did that change?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

A lot of it started to change—this is just my reading—when a more commercial market begin to develop early 1970s and was pushing forward mass making.

Western thinking is that the "better thing" is somewhere else other than your land, which is something that doesn't parallel whatsoever to the most important things in indigenous culture. Sixty years ago, there was no need for money. You'd get a lot of food from the harvest. The majority of the people in the community would grow corn, beans, squash, tomatoes, and collect the chapulines [a type of grasshopper] for trading. If you might not have something, the neighbor has it. That simplicity of life that was extremely important.

Obviously, things have changed. A lot of us have migrated to other places so we've had contact with other ways of living. Many people have begun to use chemical dyes because of the demand for more mass production.

THE KINDCRAFT

Where did that demand come from?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Tourism started to arrive and, also, wholesalers and trading posts. If you're a wholesaler, you're looking to buy a massive amount of product for the best price. So that's where all mass making begins to develop and, obviously with that, whatever you can do to make it cheap is what you going to do.

What were the effects within the community when more people started to go in that direction?

As these markets began to take force, there was a shift from using just what mother nature gives us for food and trading and so forth to start using more money. Economically speaking, it's a good thing. If today you compare my village to a nearby village, mine is quite wealthy because there's a lot of work.

On the other hand, mass-making is replacing the traditional knowledge of making natural dyes, of using plants for the colors, and does not contribute to any preservation of my culture. It's killing and replacing the knowledge that's been in my culture for thousands of years. It's not helping to continue or develop the talent of textile artisans in my community. In my opinion, there's a lot more to lose than what we're gaining.

This economy of mass-produced textiles probably keeps more young people in the village, but now they're not learning anything about the traditional ways?

That's exactly what it is. There's more money to send kids to school to be, say, a doctor — which is great and something the village needs — but the downside is that we're not teaching our kids the traditional way of making things so they can understand what we have and, hopefully, value it. For me, I had to leave my town so I could understand and discover who I am and be mindful about myself as a native Zapotec.

NO ONE TOLD US WE WERE ARTISTS

THE KINDCRAFT

In your case, you left when you were 18 to live in the US. What was it like to leave the village? Did that experience change the way you looked at all of that tradition?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I was born part of something with such a rich history and culture, but I had nothing to compare it with. We were just farm workers making textiles — Artesanías. I looked at weaving like any other job. No one told us that we were artists.

I was like any other kid — just living my life, doing creative things, and learning from my family. I was eager to learn and explore the world which, I think, is also common for teenagers... so I made the decision to come to the United States.

As soon as I got here, I started working — mainly at restaurants and, later, as a manager at a concrete company running one of the plants. I guess I was one of those kids always eager to learn new things and to ask questions and poke around. I wanted to understand how a company runs: How to hire people and do inventory control and all these other things. I got into that, not specifically looking for a management position but just because I wanted to better myself.

At that time, communication was very difficult: There were no cell phones and only one telephone in the village where I could call my parents. I decided to immerse myself and to make this place home. It took me ten years to be able to go back.

COMING HOME

THE KINDCRAFT

What was it like to return to Oaxaca after all that time?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

When I returned to my village, there was a little bit of culture clash because, in the United States, everything is at your fingertips. But what really intrigued me was, arriving home and seeing my parents' eyes and faces, it confirmed to me that we were part of this incredible culture.

My culture goes back thousands of years. People walk the same streets as my ancestors did. The food we eat comes from land where our people have grown for thousands of years. In the United States, you'd probably get mad if it rains because it was supposed to be a sunny day and you've got your suit on or you were supposed to have a party. In Oaxaca, it's a celebration because when there's a good rain, there's a good harvest.

I started to understand and connect things my parents were telling me when I was growing up. When my dad would harvest the corn, he would pick the biggest and the best pieces and put some on the altar. Now I knew why. Because that food is sacred to us — the corn, the beans, the squash — and so we make an offering as a way of saying thank you to the greater being.

THE KINDCRAFT

Once you returned to Oaxaca, did you know that you wanted to join the family weaving business?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

That happened gradually. I can clearly remember leaning against my dad's loom and talking about life while he continued weaving. In the rhythmic process of weaving and talking to him about the designs, I began to understand what an incredible art form it is. Those ideas slowly emerged within me and, almost like having an epiphany, I discovered that I have a passion for weaving. It wasn't about business. It wasn't something like "Oh, I can take these and make money!" because, if it was that, I could be one of the mass producers and probably be a millionaire right now... [LAUGHS]

THE KINDCRAFT

You found that you really missed weaving.

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Yes. This is an incredible art form and, as I reintroduced myself to my culture, I came to understand that my journey would involve the art of weaving. The only thing I really knew is that I wanted to weave. I wanted to find a personal expression within my weavings and also to honor the old ways of natural dye. We have such an incredible culture. Why are people using chemical dyes? Why aren't the old ways of making colors alive anymore?

So I told my sister Juana — who is the dye expert in the family — that I'd like to promote what we've been doing for many generations in our family, that I'd like the world to know that these things still exist. I told her that I wanted us to make every piece with the technique of our forefathers, the masters who started this art form thousands of years ago.

She said she wanted to do it, but worried that it would be incredibly difficult to go against the mass market... and against people who falsely present their work as if it's natural dye. "How can you convince the market that there's still a truly authentic natural dye?" was her question.

She's never stepped outside of the village, so she didn't know how to do it. And I didn't either. But we decided — me, Juana, and her family — to go against the odds. Together we started what is known today as Porfirio Gutiérrez y Familia studio. Every piece we make, it's natural dyes. We're reconnecting with the old ways and educating the world about them.

AGAINST THE ODDS

THE KINDCRAFT

Did you know how difficult it would be?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I've always known it was difficult and, as I get into it more, I find it even more difficult. We create the work with great honesty because we feel that the greater being will bless you when you're honest and do things with your heart. But also — you're respecting your own culture, you're respecting the people that are buying your piece, you're respecting your community. When I first promoted the work in the United States, trying to find a market, 99 percent of the shops would say "Oh yes, we have naturally-dyed Oaxacan textiles." I'd look at them and they were chemical dyes. Shop after shop. All of that was just...

THE KINDCRAFT

Demoralizing?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I went out one day after my regular job, trying to offer our goods and... nothing. Every place I went said "I have natural dyed textiles that cost next to nothing" and I almost teared up because they weren't really naturally dyed. It honestly felt like me against the world and all those people who would say anything just to sell something.

For other people, it might not be such a big deal to lie. For me, it's a big deal because this has to do with my identity. This has to do with my culture. This has to do with the respect of my community and my country and my village. So it's a big deal to me that people are lying because it makes it harder for the few people who are trying to keep these traditions alive. It's the most difficult thing that I think I've ever dealt with in my career as an artist.

THE KINDCRAFT

How did you push through?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I think going back to discovering your identity and understanding what you're doing is not just selling rugs or making money. It's passion and the love you have for what you're doing. If you don't have that, you're going to walk away. I could just go buy chemical dye rugs and sell it, right? Do it just like everybody else does. No big deal. Right? But it's the passion — in my case, it's realizing who I am. My culture. Being mindful about the importance of it. That's what makes the difference. Educating an audience to make a better choice. Making an audience that would like to support these practices.

NATURALLY DIFFERENT

THE KINDCRAFT

What makes naturally-dyed products different?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

The colors are very subtle and you're only going to see very few pieces. Sometimes we make three pieces, four pieces a month. It's because also the process of dying the yearn. To give an example, it could take us almost a year to make one color: Waiting five to six months for the wild plants that we use to mature so we can harvest them. It takes about four to five hours just to hike up into the mountains to collect them, then three weeks to dehydrate the plants and almost another week to dye them. Then we wash and dry them and — only then — they'll get to be woven. Depending on the size and the intricacy of the design, it could take a week to a month to weave just one piece. So starting from scratch, we're talking about seven to eight months per piece minimum.

It's just visually a better quality of piece. We aren't making 300 rugs at a time. With such a labor-intensive process just for making the dyes, a weaver is not going to undo that by using a cheap synthetic wool. You're obviously not going to do a sloppy job on the loom. You might work with more thread count per inch to make a better weave.

They're not cheap, but it's not expensive at all once you understand the process and the labor that goes into it. Anywhere in the world, you're going to pay more for something made by hand and made with natural dye and quality materials. You are also going to be able to understand why it costs more just by talking to people and understanding their knowledge. Juana has been building on the basic dyeing knowledge that she learned from my parents. Starting with ten shades of colors from natural dye, she's now able to obtain 50 or 60 different shades with natural elements.

SURVIVING AS A SMALL MAKER

THE KINDCRAFT

We profile many people trying to find business models to sustain their small batch production — or smaller brands who are trying to compete against mass-market retailers. I think you make a great case for the cultural context and for the quality of your product, but can it survive if you're only targeting the luxury market?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Yes — that's just how it is because of the price point... but, not only that, we sell to people who understand what we're doing and why what they're buying is special. I used to worry about it at one point, but not anymore. I think people there's plenty of people who appreciate what we do. And I don't need to sell a hundred rugs a month though, of course, the number depends on the cost of living of the country you're living in. But I think the answer is finding the right market and educating the audience — because people definitely support you if they know what you do.

THE KINDCRAFT

It also seems like you've turned education into its own business. Part of how you keep the studio going is by doing workshops and travel experiences, right?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Yes. We've been finding other ways to bring in money without upsetting the quality of our dye process. We started a project three years ago to create a dialogue between masters — not only about our technique or process, but also including ceramicists, silk weavers, cotton weavers, backstrap weavers, and embroiders. Oaxaca has so much to offer and my idea is to create a dialogue and invite the world to come and learn from these masters, take workshops, study, paint, and photograph. It's been incredible.

The reason why people come to an Oaxacan village is because of the Oaxacueños: Our indigenous practices, our language, our way of life, our ceremonies, our food, our villages, our land, our history. These projects are about telling our own stories. It's bridging us with the world. Why not give the world an opportunity to come and learn and stay and eat at our table and learn our language and learn our practices directly from us? Why not have the opportunity to tell our own story and the make sure the economic opportunity goes directly to the communities?

SELLING TRADITION IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD

THE KINDCRAFT

This is a good moment to talk about traditional design in a global world. You're talking about inviting the world into Oaxaca to see and understand your culture and help support the work that you're doing. Has that changed your process as an artist and designer? Are you designing fabrics and products that are more "globally salable" or holding to traditional designs?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I was talking to a Navajo friend of mine about these kinds of issues. He told me "Artists are like musicians. Musicians play their music. The audience comes and listens to the music and, if they don't like the music, they walk away. " Artists create work that speaks to your soul. That speaks to your vision, that speaks to your time and to the culture of where you come from. I'm aware that not everyone's going to like it, but I'm also aware that there's going to be people who'll love the work I do.

So that's how I approach it. I don't specifically pay attention to trends because... it's going to drive me nuts! Instead, I research within my soul. I meditate about things a lot — the design, the concept behind the design, the story of I want to say within the piece — and I let that sink in and ferment, just like our dyes. A design for a piece of art could come to life within a few months or sometimes years. I just let that be.

I'm also guided, I suppose, by my elders and the great masters who came before. I think my role is to continue to promote and educate and to continue teaching young weavers in my community. I have an incredibly blessing to be in my time, to be passionate about modern art, conceptual art, and modern architecture — but also I have such a great honor to be part of an ancient culture. My work creates a dialogue between these two worlds.

THE KINDCRAFT

Are you trying to bring modern ideas back into traditional making?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

In our studio, we have a solar panel now so we don't burn as much wood. Two years ago, we started a community project to teach young weavers the process of natural dyeing because, if you're not teaching young weavers and you don't have a market that will sustain these goods, it will disappear. if you don't have one or the other, these will be gone. We're also starting a dye garden soon. In terms of our consumption of plants and fruits, I think it's important to not take from Mother Earth any more and also have a place where people from our community could come and learn about these plants.

THE KINDCRAFT

Have you ever collaborated with designers outside your community?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I get approached every day. The majority of these people are coming in to make money — many of them talk about "cultural sensitivity" and "sustainability", but those are often just words. So I'm very cautious about who I work with. I have to feel the project and understand the energy and the reasons for it. It has to be a conversation. Respect works both ways and, if you're a designer coming in who only wants me to be your hands, I'm not able to help you with that.

We also need to respect the plants, the trees. My ancestors believed that everything that moved has a soul. Has a soul. When I was young and collecting the dyes and firewood up in the mountains with my father, he would always emphasize that the plants are alive and that we need to respect them. When I talk to Juana about it, she says her emotions get into the colors and that her faith is intertwined with her practice as an artist.

So when someone asks me to tell them the process of natural dying... well, I can't tell you the process if you don't understand that our colors came from a living source and what that means to us. If you don't understand that, it's just a color for you and I don't think you'll respect it or the people. I don't think you'll be aware of what you're looking at or what you're working with. It just becomes a pretty thing to you — but there's a reason behind all of these things.

THE KINDCRAFT

To what extent do you also define yourself as a member of a global community for indigenous craft, natural processes, and sustainability?

Porfirio Gutiérrez

I haven't really thought about where I stand in this community, but I'm definitely aware that I am part of it — and I want to make myself part of it. I'm starting to realize that there are passionate people just like myself around the world. I'm hoping to spend some time in India in the near future and Aboubakar Fofana and I have talked quite a bit about spending some time together in Oaxaca. Hopefully more of us can come together to learn and talk more and strengthen this global community.

Overall, I think humans have a need to reconnect with simple principles with nature — with real food, with real things — so it's good timing! There's starting to be strong interest all over the world for things that are handmade and food that's "farm to table". Little by little, it's definitely starting to turn the direction of things.