For textile artist Wisanee (Ying) Wattanavichien, it was a chance experience at a workshop that opened her eyes to a hidden thread running through the fabric of her life in Thailand.

Here, she traces that thread – the role of fermentation as a foundation of culture, cuisine, and craft — from her childhood memories to her current work with natural dyes in northeastern Thailand.

Connecting the Dots

The phrase "life is connecting the dots" truly resonates with me as I think back to my childhood: I grew up in many parts of Thailand, and since I was a kid, I noticed that almost every meal, anywhere, included at least one fermented ingredient—whether it was sausage, vinegar, or shrimp paste. My family knows how much I love the savory taste of fish sauce. I'd often see beer, wine, or whiskey on the table too.

These are all examples of fermented products deeply embedded in Thailand’s culture and food cultures around the world. Fermentation is the process where microorganisms like yeasts, bacteria, and molds break down substrates such as proteins and sugars into byproducts like amino acids, alcohol, or acids.

There are more microbial species on Earth than plant and animal species combined. These microbes produce different results, affecting the taste and color of fermented foods in remarkable ways.

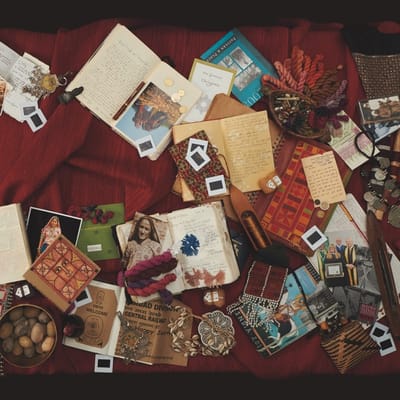

Photos by Wisanee (Ying) Wattanavichien

Returning to Sakon Nakhon

In late 2021, after graduating from architecture school and starting a small handwoven textile business in Chiang Mai. I relocated to my family home in Sakon Nakhon Province, where I inherited a garden. I'd only lived in this province for two years during my teenage years but, during childhood, my parents often took me there on vacations to visit my grandparents

Sakon Nakhon Province is in the northeast of Thailand—the Isaan region— is an area full of agricultural wisdom and traditional craft knowledge. Most independent artisans do their crafts when they have free time from agriculture. My grandpa was involved in agriculture, too, growing sugar cane before converting the land into a rubber garden.

Where land in Thailand is used to grow grass, rice, and sugarcane, it becomes a source for the local food supply, and byproducts like rice bran and molasses are used for livestock feed. This agricultural abundance, over time, has led to the creation of distinctive foods which use the natural fermentation process — such as nham (Isaan sausage), made from pork, sticky rice, and herbs, and mham (meat sausage).

The Geography of Flavor

The northern and eastern edges of the Isaan region are divided from Laos by the Mekong River. Freshwater fish from the Mekong and inland rivers create one of Isaan's most renowned fermented ingredients: pla raa (fermented fish) made from fish and salt.

When I was a kid, I remember visiting my grandma and seeing a room full of jars containing homemade pla raa, stocked up for daily cooking and giving away. I'd also see her neighbor walking by, pushing a wooden cart filled with pots of pickled vegetables to sell at the market. These were fermented with rinsed rice water and salt.

Salt is key to most fermented dishes in Isaan. Local Isaan salt comes from saline groundwater—a legacy of the Mesozoic era when the plateau was submerged under the sea millions of years ago. When I lived in Rayong and Chantaburi, coastal cities in the Gulf of Thailand, there were similar ingredients to pla raa—fish sauce and shrimp paste, fermented with sea salt. Drive along the coast and you'll spot sea salt farms.

Photos by Wisanee (Ying) Wattanavichien

The Moment of Connection

A soy sauce tasting workshop a year ago was the moment when I began to understand how fermentation was a sort of hidden thread, running through so many elements of Thai culture.

A Japanese company brought their fresh soy sauce to the event and gave a presentation about their traditional koji (the microbes used for fermenting soy sauce) — and how they had designed an architecture that created an environment specifically suitable for the microbes.

In the same workshop, we also discussed fish sauce as a staple of Thai cooking. We tasted varieties made from sea fish and freshwater fish, as well as ones using salt from underground saline sources and sea salt.

There was a guest speaker who was a wine sommelier that became interested in fish sauce during the pandemic as she started cooking more at home. She mentioned the concept of terroir, a French term that describes the environmental factors affecting a crop's growth and, eventually, the flavor of wine. Perhaps this concept can also apply to fish sauce, as fish and salt from different sources could produce different tastes.

Later, I read The Noma Guide to Fermentation which mentioned the concept of "microbe terroir." That's when I started connecting the dots in my head again! Our bodies aren't single entities—they're home to diverse microorganisms, especially bacteria known as resident flora or microbiomes. I once heard that eating local fermented dishes when traveling helps your stomach adjust, which aligns with how probiotics and prebiotics support gut health and overall well-being.

From Food to Fiber

Understanding fermentation brings us health, but it also enhances the aesthetics of indigo dye. The process of creating natural indigo from plant to paste relies on magical microbial processes inside a live fermentation vat. Indigo leaves are soaked, combined with natural materials like fruit sugars, and fermented at specific temperatures. Microorganisms feast on organic materials, creating a reduction that transforms blue indigo into yellow-green "leuco-indigo."

Photos by Wisanee (Ying) Wattanavichien

This living vat requires continuous nurturing. When dyeing, we dip cotton or silk yarns multiple times, allowing oxidation between dips as blue layers build deeper and darker. Beyond indigo, fermentation creates other natural dyes like ebony, made from fruit rind and wood tannin.

A well-cared-for vat can last decades, becoming a cherished tool passed down through generations. The balance of artisan skill and microbial activity highlights the connection between nature and textile beauty—another thread in the fermented fabric of Thai life.

Photos by Wisanee (Ying) Wattanavichien