Textile artist and educator Ragnheiður Þórsdóttir has impressive credentials: A graduate of the Art Academy of Iceland who studied experimental textiles at John F. Kennedy University in California, she also holds a Master’s degree in art education from the University of Akureyri and has taught weaving and tapestry for over 25 years.

But her years of study and teaching have, in effect, brought Ragnheiður full circle. In her role as a weaving expert for the Icelandic Textile Center, she returns to the place where her own grandmother taught crafts a generation ago. Contributor Marian Reid learns how Ragnheiður’s professional journey to bring craft forward led her back to Iceland’s traditional culture of weaving and storytelling.

“Everything in weaving is connected to stories. In the old days, you would weave your life. What you wove is how you would spend your life. The warp is what you were given and the weft is what you would do with your life. You would spin something out of nothing, like an alchemist.”

Sitting with Ragnheiður (“Ragga”) Þórsdóttir in the loft of the Icelandic Textile Center, we perch among old wooden looms and look out the attic window to a piercing blue sky and an equally blue river that carries pale sheets of winter’s last ice into the Bay of Húnaflói.

The bulky wooden structures that surround us are the very looms Ragnheiður herself played under when she was a child, long before the Textile Center established itself in the little town of Blönduós, in Iceland’s far north.

“My grandmother taught here when it was a women’s school.” Ragnheiður says she would sometimes accompany her on days when she was teaching. “She taught me to sew, embroider, crochet. She didn’t teach me to weave, though.”

‘Mjaltastulka’, Daniel Bruun 1897. Woven woollen clothes worn by Icelandic farming women in the late 1800s.

Traditional Icelandic embroidery at the Icelandic Textile Museum.

Iceland’s Textile Tradition

Ragnheiður thinks the reason is that weaving was on the decline when she was a girl. Although there are still weavers in Iceland, there aren’t many – something she thinks is damaging for future generations. The weaving tradition, she says, holds a key to so many narratives from Iceland’s past.

According to the Icelandic Textile Museum – which sits in a small building alongside the Textile Center – Icelanders have spun and woven wool for over 1,000 years. From the middle ages, women worked at warp-weighted looms in single-room turf farmhouses (baðstofa), making clothes, bedding, and riding gear over the winter.

This practice increased in the 1600s when Denmark imposed a trade monopoly. Iceland was forced into a period of self-sufficiency and, as a result, the tiny nation’s economy was built on farming and wool. Weaving became Iceland’s main export to the world until the 17th century, when fishing and industrial textiles took over.

The Icelandic Textile Center is one of the last keepers of this weaving tradition — but it’s also a place that cultivates makers of the future. For the last four years, Ragnheiður has been repairing the old, countermarched looms there – the same ones she played under as a girl – while researching traditional weaving patterns. From time to time, she teaches Icelandic and international textile artists who visit the center as artists-in-residence.

For Ragnheiður, the practice of weaving is a lot like storytelling.

Woven Folklore

Ragnheiður explains how you can find life narratives in Iceland’s most decorative weaving, much of which is linked to folklore. Saddle blankets, for example, were woven with a special technique called Icelandic glit (brocaded on the counted thread). The imagery in the weaving represented the flowers often found around farms and communities.

“These flowers can be found in the nature and, when a woman would travel, the flowers and nature would wrap around her in the design and protect her,” she says. “These kind of flower patterns are called ‘flowers of life’, similar to ‘tree of life’ patterns.”

Saddle blanket woven in the Icelandic glit technique at the National Museum in Reykjavik.

A collection of belongings from Halldóra Bjarnadóttir (1873-1981), housed at the Icelandic Textile Museum.

Examples of woven wool cloth at the Icelandic Textile Museum.

Old weaving designs also contained useful knowledge for life, with many patterns representing traditional medicine, and other uses for leaves, teas and natural dyes.

“My great-grandmother was a midwife and she would sometimes go up in the mountains picking herbs. Some of the weaving patterns are connected to that. They tell you what the plants do for your health,” she says. “It’s a circle, it’s all connected. The sheep eat the herbs and grasses, they make the wool, we weave the wool, we pick the flowers, that make the dye baths to dye the wool.”

Weaving and stories were often intertwined with some Icelandic songs and poems, which Ragnheiður says were actually instructions for weaving.

“These old poems and songs are mostly from the time we wove on the warp-weighted looms, and we have several teaching poems from the 13th, 16th and 17th centuries – like Darraðarljóð or Króksbragur,” explains Ragnheiður. “They describe how to weave on the looms, how to fix a broken thread and so on.”

“We used to teach children through songs and poems because back then people didn’t write things down. Icelandic rhymes are full of textiles.”

Reinvention of Tradition

Ragnheiður says she is starting to see more Icelanders becoming nostalgic about the practice of weaving, and interested in rediscovering traditional techniques.

Hand-spun Icelandic wool.

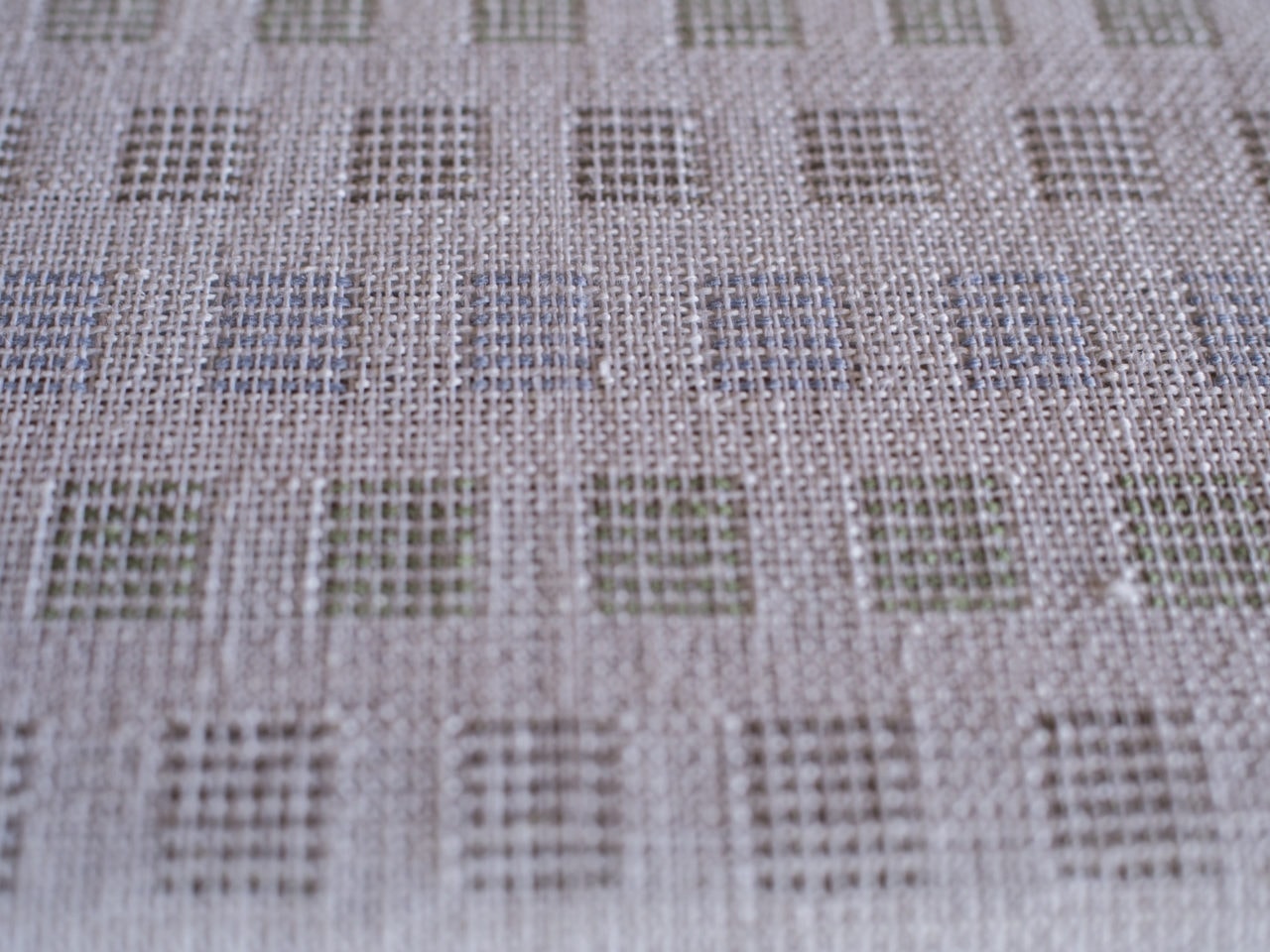

New weavings on old looms by Ragnheiður Þórsdóttir at the Icelandic Textile Centre.

New weavings on old looms by Ragnheiður Þórsdóttir at the Icelandic Textile Centre.

Example of traditional loom weaving at the Icelandic Textile Museum.

“People have an idea that weaving is calming – that the act of weaving is your heartbeat heard in the ‘click click click’ of the loom,” – this click being the rhythmic sound once produced by river stones hung from the warp-weighted looms for tension. The stones themselves were precious because they had natural water-worn holes through the middle and were only found in the highlands.

“Now I just use a drill,” says Ragnheiður with a laugh.

These days, most of the weavers who sit at the looms at the Textile Center in Blönduós are textile artists from around the world learning how to work Iceland’s traditional weaving styles into their own individual techniques.

Ragnheiður would love to see more Icelanders introduced to the process of weaving and textiles as children, she says, believing this knowledge essential for the wellbeing of future generations.

“Something is happening in the world – weaving is getting very popular. People are beginning to understand that we have to teach children to work with their hands. We cannot cut the thread between the brain and the hands.”

To Learn More…