Basketry is, in many ways, the original textile art. Predating the weaving of cloth, basket-making skills were used to make almost everything that human beings needed to survive: Houses, fences, furniture, cages, boats — all depended on basket-making techniques which, in their time, straddled the line between craft and technology.

Though new methods of building and making eventually emerged, there are places where the old ways endure. Writer/photographer Cindy Fan recently traveled to Djerba, a small Mediterranean island off the coast of Tunisia, where she found a basket-making artist still practicing this traditional handicraft.

Driving from Djerba airport, it doesn’t take long for a visitor to notice that palms dot the island. Sprouting from the dry, sandy earth, each plant is a starburst of tough spiky branches. For centuries, artisans have been transforming palm leaves into baskets, mats, and more.

Walk down a street in Djerba and you’ll see men and women wearing straw hats, giving the island an unexpected tropical feel. While a practical measure against the fierce North African sun, the hats are part of traditional Djerban clothing. The island’s museum explains that women in the northeast, southeast, and parts of the center wear a pointed hat with a wide brim. In other areas, they wear a pointed hat with smaller brim.

It’s not only hats. Palm leaves (feuilles de palmier) are used to create a variety of handicraft, both practical and beautiful.

THE ART OF BASKETRY ON DJERBA

Wander through the maze-like souk of Houmt Souk, Djerba’s main town and you’ll find Khacha Mohamed and his atelier of basketry (vannerie) and mats (nattes). The 69-year-old artisan has been making palm leaf handicrafts for 57 years, a skill taught to him by his father when he was 12. As he sits on the floor finishing a large floor mat, he explains the process to me.

Fresh, young leaves are cut off the palm and dried in the shade for 10 days. Drying in the shade ensures the leaves stay the same quality and color as direct sunlight turns it dark. Once dried, they are stripped into different widths, the pieces plaited into fans, baskets, hats and mats.

A key component to these products is cord, also made from palm. Green fiber is beaten with a rounded wood mallet until extra soft and flexible. Mohamed takes two thin strands and, securing them at one end between his toes, rubs the strands between his palms. In no time, they are twisted into a single long, strong cord which will change to the familiar yellow/brown color over time.

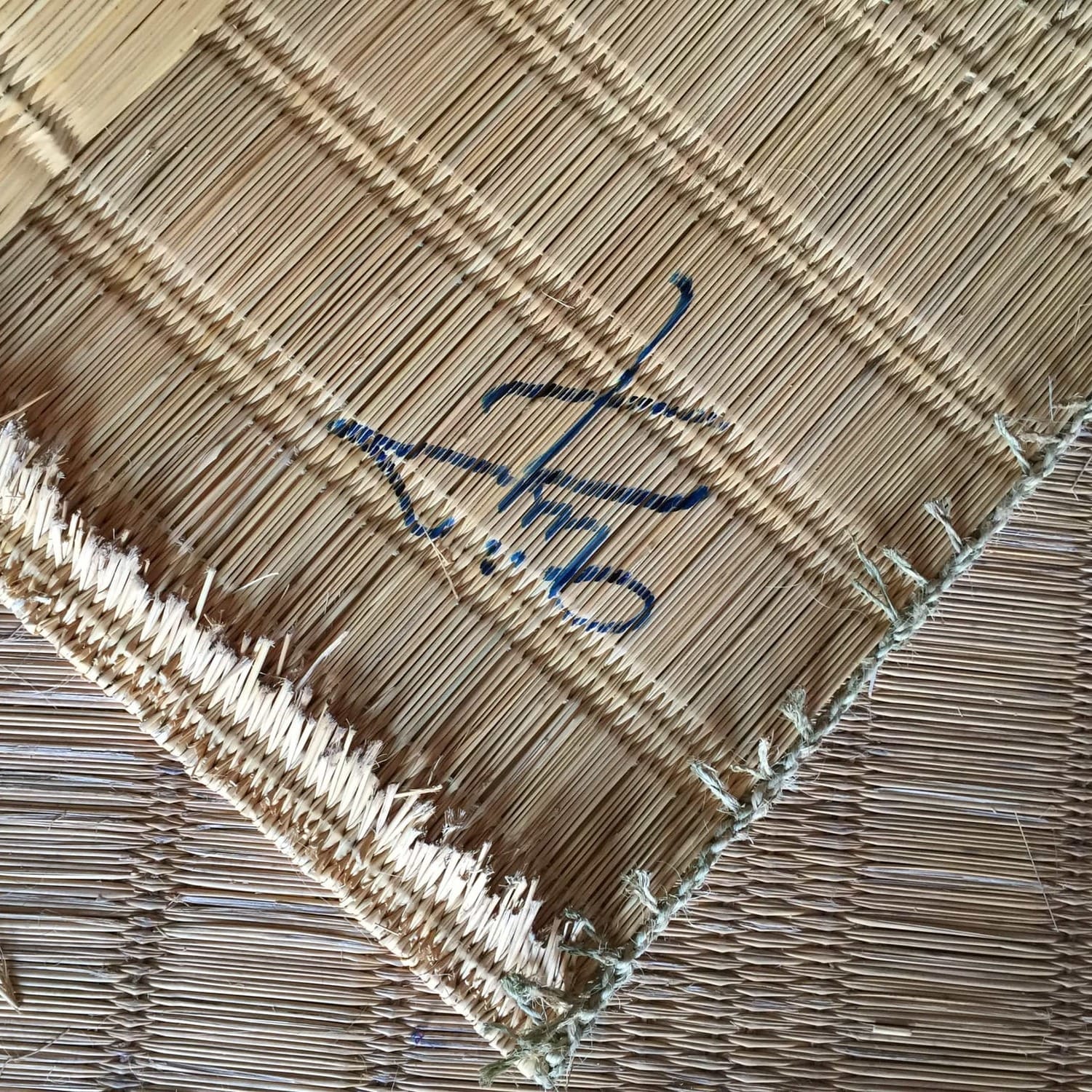

In baskets, the cord is sewn in to finish the rim as well as on the bottom. It is also sewn up the sides to add support for the handles which, themselves, are made by braiding the cord together to form a thicker, even stronger rope. A basket takes about two and a half days to complete.

The cord is also used for the warp yarn on the loom for weaving rush matting — anything from placemats and table runners to Muslim and Jewish prayer mats and large floor coverings.

This video by Djerba Insolite shows the entire process as demonstrated by another Djerba vannerie artisan, Said El Benna (Note: There are minor variations between his method and Mohamed’s).

What To Look For In A Basket

Plaiting some leaves may seem simple, but look closely and you'll see that not all baskets are made equal. Mohamed’s daughter Amel explains that, when shopping, one should look at the evenness of the weave and only buy products sewn using palm rope — not made of anything else like nylon thread. For best quality, the natural material (without dye) will be light in color, not dark or green.

A good quality product will be strong, yet flexible: Placemats can be wiped down with water and baskets can be pressed flat without breaking and then transported in luggage, springing back into shape once the journey is over. Mohamed tells me a customer recently visited and showed him the basket she had bought from him 10 years ago — it was still fine.

Mohamed has taught the craft to his three sons, but they aren't interested in continuing on the tradition. This scenario, not uncommon in many parts of North Africa, also affects Djerba's artisans and so basketry has become an endangered craft. Another challenge for local makers is that, like the rest of Tunisia, tourism to Djerba crashed in the wake of the 2011 revolution and subsequent terrorist attacks in Tunis and Sousse. Though there are signs of recovery, business in the souk remains a shadow of what it once was. Buying from artisans like Mohamed encourages the craft to survive.

Mohamed explains that he believes the palm is the “tree of luck” and ties a string of palm cord around my wrist, reminiscent of baci blessing ceremonies I frequently attended while living in Laos. Finding Mohamed, learning the process, and taking home one of his baskets already feels like a blessing.