Just two hours by plane from the busy island of Manhattan, the slightly smaller island of Bermuda sits in the North Atlantic Ocean. It's known for its pink-sand beaches and a rich, diverse culture influenced by the world over.

Bermuda’s creative community has long been a powerful force in shaping how the island sees itself and how it's seen by the world. As a British island territory, it's a place that has often been defined by outside narratives, but the island’s geographic isolation has nurtured a distinctive cultural voice — one that is rooted in local traditions and conversant on the global stage. Today, Bermudian artists are reclaiming their story and using their creativity to honor their heritage, challenge assumptions, and spark dialogue about identity and belonging.

Gombeys are one of Bermuda’s most vibrant, colorful, and enduring cultural traditions blending African, Caribbean, and Indigenous influences. Photos by Allison Milewski.

Art for the Body

Bermuda's commitment to art and identity is reflected in Hamilton’s City Hall, a civic space deliberately designed to include the Bermuda National Gallery and the Earl Cameron Theatre, exemplifying how art and culture are integral to the island’s public life. This spirit was on full display during Art for the Body: A Discussion on Wearable Art, held on May 30, 2025 during an exhibition titled Meditations on Form: Jewellery by Melanie Eddy.

Moderated by BNG Executive Director Jennifer L. Phillips, the conversation featured three Bermudian artists — Melanie Eddy, Courtney Clay, and Jordan Carey — who explored how their work embodies memory, protest, and cultural resilience. Through jewelry and textiles, each artist revealed how the arts in Bermuda are preserving stories, resisting erasure, and envisioning new possibilities for the island’s future.

(Top, right) Bermuda National Gallery at Hamilton’s City Hall (photo by Allison Milewski) during Art for the Body: A Discussion on Wearable Art on May 30, 2025 featuring BNG Executive Director Jennifer L. Phillips (top right, seated on the left) Melanie Eddy (bottom, left), Courtney Clay (bottom, right), and Jordan Carey (top right, with mic). Photos by Brandon Morrison, courtesy of Bermuda National Gallery.

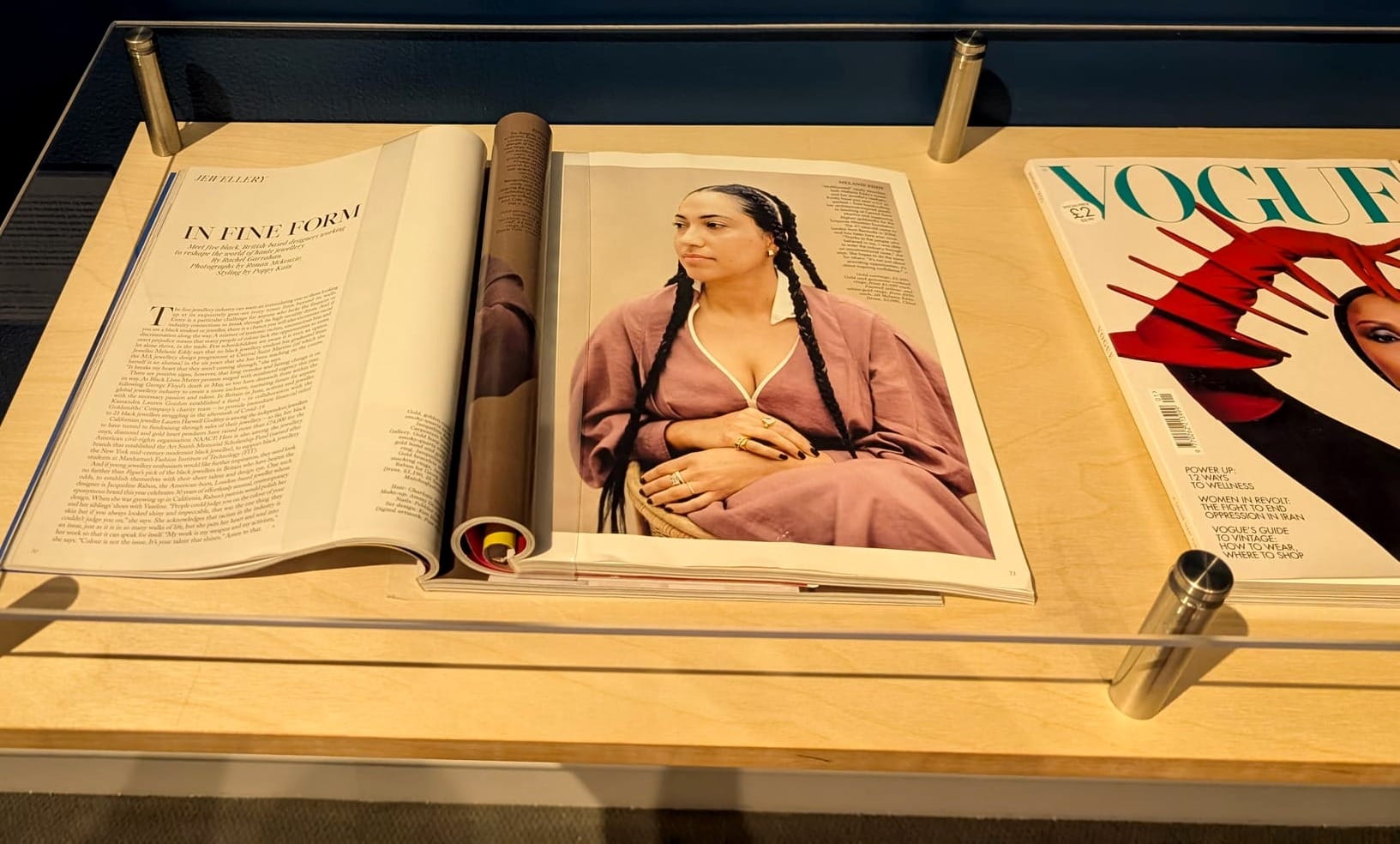

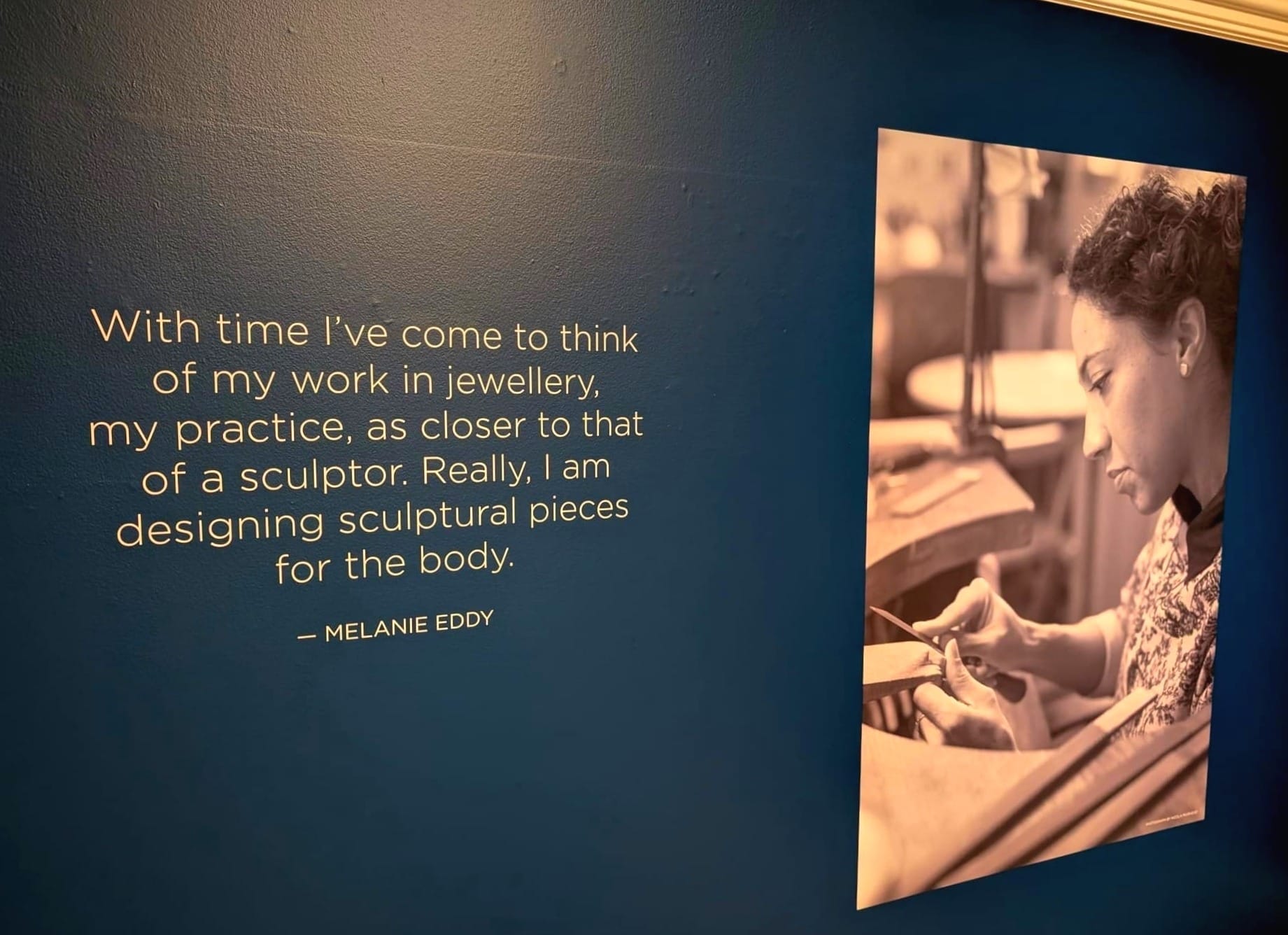

Melanie Eddy: Crafting Freedom Through Form

Melanie Eddy is an accomplished sculptural jeweler and native Bermudian whose work has been profiled in The New York Times and British Vogue. Having earned an MA in jewelry design from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London, Eddy is interested in how the many characteristics and historical elements of Bermuda inform her work, but like any artist, Eddy's story finds its way into her pieces. She seeks inspiration from her family’s cultural heritage of stone-cutting, sail-making, and whaling dating back to The Age of Sail in the 15th Century, when the world was just beginning to discover just how big the globe is.

Meditations on Form: Jewellery by Melanie Eddy at the Bermuda National Gallery.Photos by Daniel Broderick

Eddy pointed out during the Art for the Body talk that jewelry, as a status symbol, has placed restrictions on who wears what and it's often based on assigned traits like class, hierarchy, and gender. She has worked to dismantle those divisions by focusing on accessibility and flexibility. “I try to design pieces in silver or accessible stones that still carry meaning, intention, and connection to place,” she said. Eddy designs her pieces without fronts or backs and encourages people to wear her jewerly however they please. That “freedom of form,” as Eddy put it, “is essential to my approach. Jewelry has always been about more than decoration. It’s memory, status, protest, and identity — all wrapped around the wrist or finger.”

Her path as an artist wasn’t exactly straightforward, and it’s taken a lot of trial and error to hone the process she uses today. “There was a time I created complex systems for making jewelry because I felt I had to justify my place in the design world,” she said. Letting go of that rigidity turned out to be an act of resistance in and of itself, and she’s found that eliminating those self-imposed constraints has come with a shift in her work. “I no longer carve with training wheels… Before, my elbows were out. Now my shoulders are down. I’m more grounded, and I’m making space for new possibilities.”

Courtney Clay: Dressed in Identity, Wrapped in Legacy

Multi-disciplinary artist Courtney Clay studied across the U.K at the University of Creative Arts Rochester, Kingston School of Art, and the University of the Arts London, yet her work throughly captures the spirit and colors of Bermuda. Her distinctly Bermudian aesthetic landed her an invitation to design ties, scarves, and pocket squares for Team Bermuda during the opening ceremony of the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris. Clay's print designs for Team Bermuda featured abstract swirls of pure blue ocean water, like waves and tides, and bright pink sandy beaches.

She called the design process for the Bermuda Olympic team uniforms a “power experience,” especially “knowing every woman involved in the design team was a woman of color” and that those women were “taking up space where we hadn’t been before.” While Clay was quick to point out that “people love to critique, especially when it comes to national symbols,” she added that the project was a welcome exception to the colonialist mindset, saying: “To create something expressive, abstract, and Bermudian for that stage was an honor and a statement.”

(Top) Images of the Bermuda Olympic team accessories by Courtney Clay (Bottom) Collection images via courtneyclaystudio.com

Not unlike Eddy’s jewelry, Clay’s work is “About access and power through adornment.” As both an act of resistance and a way to create generational legacy, “Scarves became the answer because they’re a statement anyone can wear, no matter your gender or status,” she said. “Scarves made sense because I could see my mom, my dad, even my grandmother wearing them. They’re made to be passed down… Even my dad wore one of my scarves the other day, tied cowboy-style, and told everyone about it.”

Ideally, the generational legacy Clay hopes to create will go beyond her immediate family. “My dream is that someone will look at my work and say, ‘If she did it, I can too,’ regardless of where they come from. This isn’t just about me. I want the next generation to see what’s possible when you believe in your own story.”

Jordan Carey: Designing for Impermanence

Jordan Carey is a designer and artist who was born and raised in Bermuda. Even after living in the United States and gradating from the Maine College of Art in 2019 with a bachelor’s degree in fashion and textiles, Carey's art remains heavily influenced by his Bermudian upbringing. Working with naturally-dyed textiles that feature island-themed prints, his art is rooted in Bermudian craft traditions like dyeing and kite-making.

Jordan Carey in his shop. Photos by Allison Milewski.

Unlike his colleagues on the discussion panel, Carey is not at all concerned about his tangible products lasting forever. “I’m not attached to the legacy of objects,” Jordan said. “Some pieces are designed to be destroyed, reused, or worn into disappearance. Even my works on paper are meant to break down. Handmade paper, natural dye, fibers — they're all ephemeral materials that carry meaning as they age. Just because something doesn’t live in a static existence doesn’t make it less valuable.”

This perspective informs Carey's art as his own act of resistance. “That, to me, is a form of protest — against permanence, against systems of ownership, against extractive value structures in art and fashion.” His philosophy is reflected in Loquat, the fashion brand he founded with retail store locations both in Bermuda and Portland, Maine. Even as a small brand, “I’ve turned down commissions where I felt we weren’t on the same page,” Carey said. “If the values don’t align, I won’t move forward. That’s part of the practice.”

While their choice of medium may vary, all three artists create work that shares a vision of Bermuda that is locally-minded and global conversant. They are united in using art as both archive and as a resistance by crafting pieces that carry memory and assert identity. From Eddy's sculptural jewelry, to Clay's printed scarves she hopes will last for generations, and Carey's textiles that embrace impermanence, these artists exemplify how creative Bermudans are reclaiming a narrative with work that simultaneously looks back to their heritage – and forward towards the future.